USCG Propeller Guard Test Procedure – an initial review

We have since had time to quickly read through it and have a few comments:

- Speed vs. RPM every 500 RPM and top speed

- Acceleration / Deceleration

- Bollard Pull

- Maneuverability

- Ease of Installation

- Effectiveness

- Speed vs. RPM every 500 RPM and top speed

- Maneuverability

- Ease of Installation

- Effectiveness

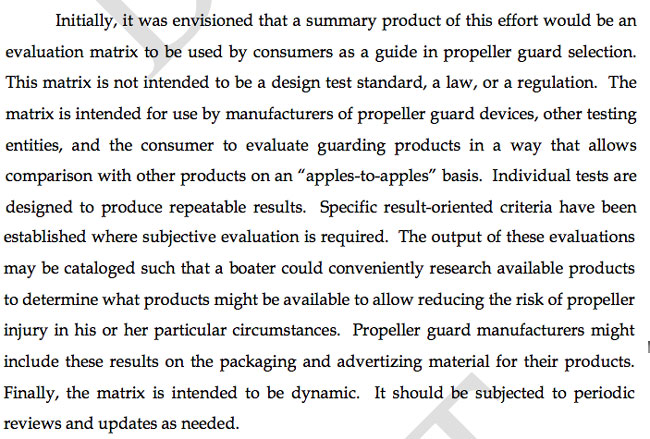

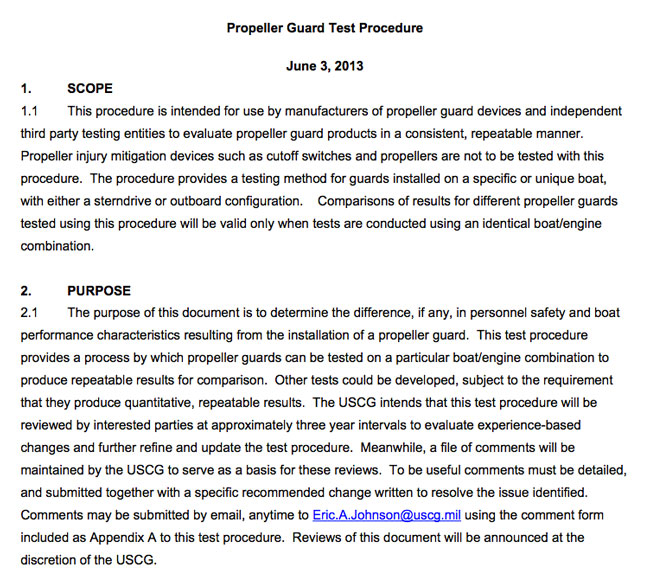

1. The entire document appears to have been re-written since the October 2012 version. A quick comparison of page 3 of the new version and corresponding portions of pages 2 and 3 of the old version (both versions shown below) make that pretty obvious.

The October 2012 version below talks about the tests being a way consumers could evaluate propeller guarding products, and how manufacturers might include test results on their packaging and advertising materials. They say its purpose was “to evaluate the essential safety consequences of installing a propeller guard on an outboard or sterndrive boat.

The new September 2013 version below says its for testing a specific guard on a specific boat. Comparisons with other guards will only be possible if they were tested on an identical boat/engine. The test is to determine the difference, if any, in personal safety and boat performance when the guard is added.

We also winced a bit when the procedure said that to compare two different devices they would need to have been tested on an identical boat/engine. In court the industry often refuses to accept tests on identical boat/engines. They say it has to be the same hull as each hull has its own slight differences.

Summarizing, their earlier protocol was to be an aid for consumers in selecting a propeller guard, while the new procedure is for determining the difference in personal safety and performance on a specific or unique boat with and without the guard. That sounds like the new procedure is bound for courtroom use in determining if a proposed guard is better than no guard at all in a propeller accident case.

The new version says nothing about being an aid to the public for selecting a prop guard.

2. The new procedure Page 8 item 8.1 says propeller guard performance will be rated on a scale of 0 to 3 for each of the four categories. Just offhand we are more used to rating things from 1 to 4, but moving down one integer to zero may allow a “no change” rating.

3. The new procedure Page 8 item 8.2.2.6 appears to allow re-propping for testing with a guard if the engine will no longer reach its full RPM. That was not allowed in the old protocol.

8.2.2.6 Should the engine fail to achieve the manufacturer’s rated maximum rpm during Step 8.2.2.4 above, install a propeller with a pitch allowing full rated rpm to be achieved with the guard installed and then repeat the steps in 8.2.2.

4. The new procedure Page 9 item 8.2.4.1 explains the rating system for the Speed vs. RPM test.

8.2.4.1 Following the procedures above, a speed rating can be determined. When determining the rating for speed, a degradation greater than or equal to 25% relative to an unguarded propeller shall be assigned a rating of ’1’, a degradation of between 10% and 25% shall be assigned a rating of ‘2’, and a degradation less than or equal to 10% (or an increase in speed) shall be assigned a rating of ‘3’. Since there are a large number of combinations of potential hull forms and power, the test report shall state that the rating was based on testing using a particular hull form and engine.

Most of the tests seemed to be on a 0,1,2,3 rating scale. It is not quickly obvious why this test moved to a 1,2,3 rating scale.

5. The new procedure Page 11 item 8.3.5 will be very tough for testers to replicate without some examples (and a statistician on staff). We contend most manufacturers of boat propeller guards (typically very small manufacturing operations) will have no idea how to comparing steering torques after reading that statement which has been copied below.

8.3.5 Statistically compare the average of these peak torque measurements recorded above for a guarded versus unguarded condition to determine whether the addition of a guard significantly alters steering effort. A simple two-group comparison test will suffice (an independent t-test or Mann-Whitney test, depending on whether the data is normally distributed). Any peak torque measurement under the guarded condition exceeding 27 Nm shall result in a rating of “0” for this test. If no peak readings greater than 27 Nm are recorded, determine evaluation scores from Table 3 below.

Page 14 of the old protocol explained some of the pitfalls to lookout for when running this statistical test. That information is no longer part of the procedure, even further reducing the probability of a propeller guard manufacturer correctly completing step 8.3.5 in the new procedure.

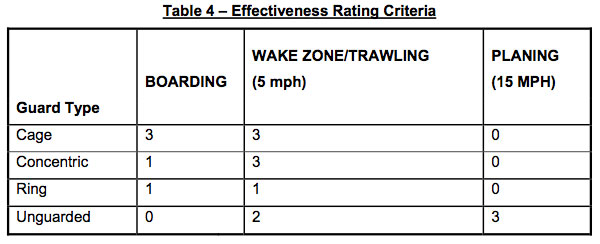

6. The new procedure Page 13 item 8.5 Effectiveness says manufacturers can just accept the rating their type of guard (ring, cage, concentric ring, etc.) was labeled with in previous testing at SUNY or they can do their own testing.

We notice no rating for swing up rear flaps / shield such as Guy Taylor’s 3PO guard.We also notice no references to our previous comments, The Emperor Has No Boat. In our opinion, testing without a real boat at SUNY renders those results not comparable to reality (drive attached to a boat). Or in their own words relating to this test procedure, “The procedure provides a testing method for guards installed on a specific or unique boat, with either a sterndrive or outboard configuration.” How can that be true when no boat was in the water at SUNY?

By the way, the propeller was not powered at SUNY either. They just swung the platform on rails around the loop while the propeller free wheeled. Any efforts to correlate the “No Guard” effectiveness data with real life would probably struggle with that point too.

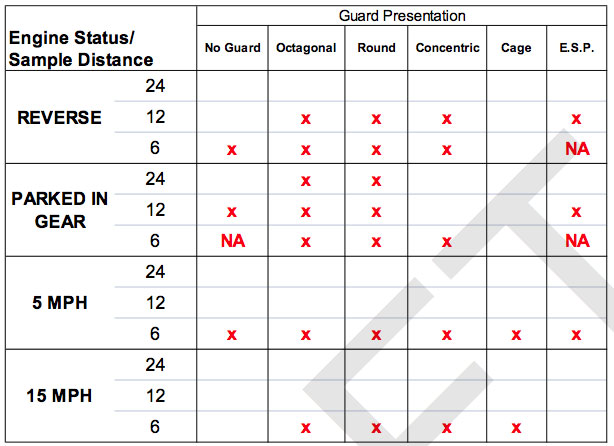

7. The new procedure Page 8 item 8.5 Effectiveness Table 4 shows a rating system form the various types of guards and unguarded propellers.

However an earlier 2011 similar table showed reverse as a separate column. The new procedure combines it into boarding along with idle and reverse.

The legend for the chart above is below:

No Guard = Exposed propeller

Octagonal = Guy Taylor’s 3PO guard

Round = Adventure Line Guard

Concentric = Prop Guard by Prop Guard Marine

Cage = MariTech SwimGuard

ESP = Australian Environmental Safety Propeller

They may have recognized that unguarded propellers have major problems vs. many propeller guards at parked in gear, idle forward, and in reverse. Then decided to minimize attention to those issues by combining all three into one rating called boarding.

8. The entire procedure is now only 13 pages long. The document sent out for review in October 2012 was 43 pages long and included many examples, data output, charts, etc. The new document is much shorter, but will take much more effort to apply consistently between manufacturers. Unless someone pops up and starts conducting these tests for a fee (like ATA or Design Research Engineering)

9. It looks like several tests fell by the wayside between the old and new versions.

As we looked through the old version, it included these tests:

However when we looked though the new procedure we only found:

The Acceleration / Deceleration test and the Bollard Pull test are noticeably absent from the new version.

We are guessing they thought the Speed vs. RPM every 500 RPM and top speed test paralleled the results of the Acceleration/Deceleration test. The Bollard Pull test results may have been relatively similar with and without guards, or even better with some of the ring guards.

10. Noticeably absent is any naming of authors. Several engineers at CED Investigative Technologies, the USCG contractor tasked with much of the development of the test protocol, were listed as authors of earlier versions.

Per USCG’s press release, the industry’s own consensus standards development group, American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) developed the “test procedure”.

This procedure will likely be used in court by the industry to try to prove propeller guards suggested by plaintiffs in boat propeller injury cases are not any good.

Developing your own procedures / standards for use in your own court defense sounds a little like the 1989 NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee report. We hope it does not turn out that way.

Its even more interesting if you go back to the early days of the development of the propeller guard test procedure. National Marine Manufacturer’s Association (NMMA) wrote this in their September 2006 report on Environmental, Heath, & Safety Compliance:

NMMA

Environmental, Heath, & Safety Compliance September 2006

USCG to Begin Evaluating Propeller Guards

As part of its rulemaking development for propeller avoidance measures, the USCG has commissioned an evaluation of propeller guards when applied under the various conditions experienced when operating a vessel. The American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) will manage the project and their staff will work with the USCG to define the test boats, identify propeller guards to be tested, create a propeller guard test protocol, and retain a consultant to perform the work.

Although NMMA is not managing this project, data from this project may be used to regulate NMMA boat builders and engine manufacturers. For this reason, among others, it is important to the Marine Industry that the proposed USCG testing produces scientifically reliable and commercially useful data. As a result, NMMA is commissioning Design Research Engineering to develop a scope of work (SOW) to assist the ABYC and USCG in this project. Upon completion, the SOW will be presented to the ABYC as suggestions from the Marine Industry regarding the minimum criteria for the evaluation of propeller guards.

The SOW will include the:

1. Identification of propeller guards that are commercially available for recreational boats;

2. Establishment of minimum criteria for the qualification of propeller guard products as “feasible”;

3. Establishment of a propeller guard test protocol to evaluate:

a. the relative safety of the guard versus an open propeller,

b. the performance characteristics of a boat with the guard in place (speed, fuel consumption, handling),

c. the durability of the propeller guard,

d. any other characteristics that affect the safety, performance or commercial viability of the propeller guard.

The USCG plans to run the protocol evaluation at Solomon Island, Maryland on September 27 and 28, 2006. The propeller guard test is scheduled to run through 2007.

NMMA thinks it is important, so they are commissioning Design Research Engineering, aka Robert Taylor, the industry’s expert witness in boat propeller guard cases, to develop a scope of work (SOW), they probably meant a statement of work, for the project. That SOW will be presented to ABYC as suggestions “regarding the minimum criteria for the evaluation of propeller guards.”

Basically, that means NMMA (the boat manufacturer’s trade organization), ABYC (the boat manufacturer’s own consensus standard organization), and Robert Taylor, the industry’s expert witness in boat propeller guards, worked together to develop the early version of this test procedure. It already sounds like 1989.

11. We turned in our public comments on an earlier version back in April 2012. As I recall, none of them appeared to be implemented in the October 2012 version. We have not gone back through them to see if any are implemented in the final version or not.

One of our comments that looks like it might have been implemented was allowing changing prop pitch when installing a guard to get the RPM back up to recommended maximum RPM. However, the “procedure” is not very explicit and we may have misinterpreted item 8.2.2.6.

12. The Propeller Guard Test Procedure document has been a long time coming. U.S. Coast Guard’s National Boating Safety Advisory Council (NBSAC) Propeller Guard workshop recommended its development in 2005, and work began in 2006.

We encouraged propeller guard manufacturers to furnish guards for testing the protocol in Maine in 2007.

A November 5-6, 2008 ABYC Project Technical Committee Report at the Product Interface PTC Meeting in Baltimore, Maryland reported highlights from the ABYC Product Interface Project Technical Committee Meeting. Items reported included this bullet point, “• Propeller Guard project – Work is almost complete on the protocol for propeller guard testing. This committee may take over prop guard protocol studies in the future.”

Five years later, it was finally released (after several major propeller injury cases went through the court system).

13. While we are glad USCG finally brought the project to a conclusion, we wonder what happened to the last round of reviews we were told about in October 2012? We received the email below on October 12, 2012 regarding this project:

Following recent briefings and our request for your review of the “Test Protocol for Evaluating Propeller Guarding Methods” the ABYC/CED team received direction from the U.S. Coast Guard to clarify the testing methods. To avoid unproductive use of your valuable time, please disregard our recent request for peer review. We plan to make the requested adjustments and submit a revised draft for peer review in the near future. The peer review request and updated draft will be distributed by email to the same distribution list as the October 4, 2012 request.

We sincerely regret any confusion or inconvenience and look forward to your review and suggestions on the next draft.

We do not recall seeing any review opportunities since then. The document underwent a major rewrite since then, and we saw it for the first time earlier this week. I suspect a closer analysis will find most of our April 2012 comments were left by the roadside. Just like we were in their June 5, 2009 list of people and organizations with knowledge of issues surrounding propeller strikes. CED Technologies, the firm contracted to develop the protocol listed thirty individuals with knowledge about propeller guard issues, we were not mentioned. We suspect propeller safety advocates are probably not very high on ABYC’s Christmas list.

Reviews of the Propeller Guard Test Procedure by Others

We created this section to link to reviews and comments by others. To date, we have seen none.

Only a few publications (mostly USCG related or news aggregators) have posted a link to the USCG news release as of September 15, 2013.

On 16 September 2013, Soundings Trade Only (STO) posted a nice discussion of the release of the guard test procedure titled, ABYC and Coast Guard Join on Propeller Guard Test.

STO’s coverage of the release of the test procedure includes comments from John Adey (ABYC president), John McKnight (NMMA director of environmental and safety compliance, Keith Jackson (MariTech Industries), and a brief mention of lawsuits including the industry’s loss in the Brochtrup case.

The article makes it sound like ABYC pretty much developed the procedure, but mentions ABYC did involve some people from MIT and some of the testing resembled Myth Busters on tv. (no mention of the many folks from CED Technologies).

John McKnight of NMMA had some of the best quotes:

“If you go over 15 mph on the boat, propeller guards create a very dangerous situation and it says that very clearly in the report.”

“A good analogy would be putting a guard on a propeller plane. People have been hit with them. It would be all right to drive the plane around the runway, but don’t try to take off or you’ll die.

And our new favorite John McKnight quote

In the past, there had been several “snake oil salesmen designing guards in their garage,” McKnight said. “In litigation, the question would be asked, ‘Why wasn’t one of these put on?’ Though we don’t endorse the document, we can live with it.”

Hello

Am I able to use some of your information on my web site here in New Zealand. There is nothing like this available to us here.

Many thanks

Maureen May

Safe Marine Ltd

New Zealand.

Glad your find PropellerSafety.com useful.

You are welcome to link to specific pages of our site, but do NOT copy our materials and post them on your site.

We see considerable traffic on our site from Australia and New Zealand. The Internet is global and they are finding the information here in their native language.

As to this specific page, you could read USCG’s new test procedure and write your own review of it.

Good luck

gary