Litigation Testing Continues in Testing of Propeller Guards by Mercury Marine / Brunswick

Litigation Testing of propeller safety devices was defined by Stephen Bolden, author of Motorboat Propeller Injury Accidents, as

“…manufacturers, in performing litigation testing, are not concerned with gathering information for the purpose of redesigning or improving a guard; rather, they are concerned with simply reporting on whatever propeller guard deficiencies they are able to demonstrate through such testing”

When manufacturers test their own products or components against certain criteria or test protocols and their products fail, those involved in the testing process often offer suggestions for improving the product. But when “legal” wants a propeller safety device tested, often against very challenging criteria, the propeller safety device fails or performs poorly in some part of the test, and nobody has any ideas of how it could be improved or ever be made to pass the test, even when the solution is extremely obvious.

We first discussed litigation testing on pages 126-127 of our analysis of the proposed houseboat propeller safety regulation. There we used Mercury Marine’s 2006 test of Robert “Bob” Hooper’s Prop Buddy guard as an example. Mercury found that while planing with the drive trimmed all the way under (NOT normally done, drives are trimmed out and they come up on plane), the small test boat bow steered. Even Mercury noted, “It was not an issue when operated at WOT (wide open throttle) trimmed for best speed.” But they still tried to make hay with their find, claiming the guard was dangerous when trimmed under on plane.

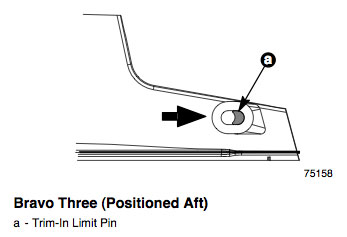

We pointed out Mercury MerCruiser’s own Bravo Three drives had exhibited identical problems back in the mid 1990s. Then Mercury Marine created some spacers called “Trim Limit Blocks” to physically limit the trim under and the problem was solved. (No more trim under too far, no more problem.)

Later on MerCruiser changed from the “Trim in Limit Blocks” to a “Trim In Limit Pin” to combat the bow steer problem and added the feature to all three stern drive models (Bravo One, Bravo Two, and Bravo Three).Below is a warning from one of MerCruiser’s manuals:

It is recommended that only qualified personnel remove or adjust the Trim “In” Limit Blocks or adjust the Trim-In Limit Pin. Boat must be water tested after removing or adjusting the device to ensure that the modified trim “In” range does not cause the boat to exhibit an undesirable boat handling characteristic if the drive unit is trimmed “In” at higher speeds. Increased trim “In” range may cause handling problems on some boats which could result in personal injury.

Now, over 15 years later, MerCruiser is still selling Bravo Threes. Yet when Mercury tested the Prop Buddy propeller guard, nobody had any ideas how the bowsteer problem could be fixed, even when all they had to do was slide the trim in limit pin OR run over and pick up some trim limit spacers off the shelf. None of Mercury Marine’s highly trained technicians or test engineers suggested this obvious solution. The comment sections on the test request are absolutely blank.

Recently we have been examining some similar instances of litigation testing in Brunswick / Mercury Marine’s testing of the Guy Taylor 3PO guard (the octagonal guard with a swing up rear shield to reduce drag when underway) during the Jacob Brochtrup propeller case.In the trial (Jacob Brochtrup v. Mercury Marine and Sea Ray, divisions of Brunswick Corporation. U.S. District Court. Texas Western District. Austin Division.) on 1 April 2010 Robby Alden (attorney for Brochtrup) had Peter Chisholm, Mercury Marine Product Safety Manager on the stand) after Brunswick showed a video clip of a boat equipped with 3PO guard leaning to one side and having some bow steering problems. Portions of the exchange are below:

I’ve got an idea, lets use the trim limit pin, put some trim limit blocks on, or otherwise limit trim under and forget the whole ^&$#! thing. Its just another example of Brunswick litigation testing. They wanted the propeller guard to fail, so it did.Q. Okay. When you performed — when you drove the boat in the video clips that are shown, I’m not going to show them again — with the one with the guard on it, that boat is already rolling or leaning to one side before you ever even start the engine, isn’t it?

A. That’s correct.

….

Q. Okay. At the end of that clip, the boat comes down flat very quickly, doesn’t it?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And the reason it came — and you’re the guy driving the boat?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And the reason it came down flat that quickly is because you adjusted the trim, correct?

A. That’s correct.

….

Q. Okay. When you drove that boat in that video, it would have been very easy for you to avoid the roll altogether, wouldn’t it?

A. As an experienced operator, yes.

Q. All you needed to do was move your thumb and change the trim, and that boat would have operated the way it should operate, just like it did at the end of the clip?

A. That’s true.

…

Q. The reason that you tend to get a little bit more lean when the boat is trimmed in or a little bit more roll with the boat trimmed in when the guard is on is because more of the bow of the boat is in the water, correct?

A. You’re asking for the cause of the roll condition?

Q. More of the bow is in the water when the boat is trimmed in, correct?

A. Yes, but that doesn’t have any impact on the — whether the device is on the drive or not.

Brunswick Corporation is not evil, Litigation Testing is what all companies due when they are presented with an allegedly safer alternative device in court. They make sure it fails the test, otherwise they are going to hammered for not using it. We have never seen a company in any industry come forward in court and say, “Gee thanks guys, your proposed safer alternative is amazing. It works great. We are going to go home and start using it tomorrow. Sorry we didn’t have it on when your client was killed.”

We noticed one more glaring instance of Litigation Testing in the Brochtrup propeller case. The first time we saw the images of Guy Taylor’s guard we saw Guy had gone a little overboard by putting a huge metal 3PO logo on the back of his guard’s flip up shield. That logo will obviously impact reverse thrust (he is choking off the inlet in reverse). Guy may have just thought that unit was going to be used for show, so he tried to put a big commercial on it? At any rate, anybody testing that unit in reverse is going to note some reverse thrust limitations.Fast forward to the same trial (Jacob Brochtrup U.S. District Court. Texas Western District), same date (1 April 2010), same lawyer (Robby Alden for Brochtrup), and same expert (Peter Chisholm, Mercury Marine’s Product Safety Director) on the witness stand. They were reviewing Brunswick Corporation’s claims about how poorly Guy Taylor’s guard performed in reverse thrust tests. Try as they might, Mercury’s test crew could not get the boat up to top speed in reverse with Guy Taylor’s 3PO propeller guard installed.

Alden got Chisholm to admit the boat without a guard on it could go so fast in reverse that you could “get the boat to a speed that exceeds what an operator ought to drive that boat in reverse at because it may cause water to come in the back of the boat or some other dangerous condition…” Alden also noted that Dick Snyder (Peter Chisholm’s predecessor) had testified that “that driving a boat in reverse, all you need to do is be able to drive it at two or three miles per hour” AND that this boat with the 3PO guard installed could reverse at those speeds.

Then Robby Alden got to my favorite place, he asked Peter Chisholm about the huge 3PO logo plate on the back of the propeller guard’s swinging shield. Did Mercury Marine think if they removed that large logo plate blocking incoming flow in reverse that the boat might go backwards faster?

Q. And it’s got this big logo plate on the back of it that adds a lot of area, doesn’t it?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And certainly in development, it might be possible for Mercury Marine to create a more hydrodynamically efficient— MR. NORWOOD (attorney for Brunswick): Objection. Calls for speculation.

MR. ALDEN: If you did research and development.

MR. NORWOOD: It’s also irrelevant.

THE COURT: It’s beyond the cross of direct and — well, I’m just going to leave it at that.

The lawyers argued between themselves a while, then the question came back in a slightly different format, and Alden was asked to restate it:

Once again, we are left to wonder how an attorney for the plaintiff (Robert Alden) was able to see that huge 3PO logo plate restricting incoming flow and wonder what would happen if you took it off, while Mercury Marine’s highly trained test crew and test engineers assigned to test Guy Taylor’s 3PO guard in reverse did not notice it. Or at least they did not suggest removing in in their test report.Q. Sure. That shield might be made more hydrodynamically efficient to improve the reverse thrust in your development process if Mercury Marine decided to produce it, right?

A. Yes. It may be possible to change its hydrodynamic performance.

Litigation testing is sometimes referred to as the testing of allegedly safer designs, testing an allegedly safer alternative, testing an allegedly safety design alternatives, or testing a proposed safer alternative.

Ultimately, the most important factor in boater safety will always be remaining alert to potential dangers. Years of experience can sometimes lull boaters in a false sense of security when operating pleasure craft.

Michael Laplante LLB

Partner, Ferguson Barristers LLP

fergusonbarristers.ca