Mercury Marine’s & OMC’s Propeller Guard Development $

The two major U.S. recreational marine drive companies of the past many years: Brunswick / Mercury Marine and Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) have been in the forefront of “debunking” propeller guards in court since the 1970’s. In this post we estimate their total expenses in developing propeller guards designed to protect people at less than $25,000 combined.

Outboard Marine Corporation was formed in 1929 from the merger of two existing outboard motor manufacturers. OMC went bankrupt in December 2000, but their insurance company still represents them against propeller injury claims.

Mercury Marine began as Kiekhaefer Corporation in 1939, and was acquired by Brunswick Corporation in 1961.

During the late 1980’s and in the 1990’s OMC and Mercury often worked together in testing propeller guards, most notably during the November-December 1990 SUNY tests. They also collaborated on legal defense efforts. Dick Snyder, Mercury Marine’s expert witness in propeller injury cases, served as an expert for OMC in several cases as well. Plus they conducted a large joint mock propeller trial in early 1989. Mercury later tried to downplay this period of legal cooperation with OMC against their common enemy (propeller injury suits). We mention this period of cooperation because it is relevant to Mercury and OMC being the major industry voices in the U.S. against propeller guards.

We (and they) have occasionally been asked how much money they spent trying to develop a “people protecting” propeller guard. The “people protecting” part is important as the industry has developed a few propeller guards which they claim were not for protecting people or were for protecting people in an extremely limited instance. Quite recently we were asked this same question again so we began to gather documents and created this post.

Other major recreational marine drive manufacturers with a substantial presence in the U.S. market are primarily the well known firms from Japan (Yamaha, Suzuki, Honda, Nissan, Tohatsu), plus Bombardier Recreational Products (BRP) from Canada, and Volvo Penta from Sweden.

Mercury Marine combined with OMC together dominated the market for a long time. Many of those legacy engines are still in service. Those sheer numbers suggest Mercury Marine and OMC will more likely be involved in propeller injury litigation than companies entering the market more recently. For example, one of our early 2012 posts used the U.S.Coast Guard Boating Accident Report Database (BARD) to estimate combined market share of outboards and stern drives in service (international’s call it boat park). We found OMC, Mercury, and Bombardier were involved in 68 percent of all BARD reported accidents in which the drive manufacturer was provided. We were unable to separate Bombardier drives out due to them still using the same model names as OMC.

Volvo Penta focuses on inboards and stern drives that tend have a much lower annual production rate than outboard motors.

The bottom line is that for many years, and even still, OMC and Mercury Marine together have a commanding share of the number of outboard and stern drives in the field in the U.S., even though OMC has been out of the picture for over a decade.

In recent years any propeller injury lawsuits involving marine drives from non OMC-Mercury players (of which Yamaha probably leads in number of units in the field) have tended to focus on:

- Other issues (boat design, over powering, PWCs)

- The boat manufacturer (injured party did not sue the drive company)

- The rental operation (injured party did not sue the drive company)

- Individuals whose actions may have contributed to the accident

Or the case settled before the performance of propeller guards was seriously debated (Coxe v. Yamaha & Maverick Boat Company).

Regardless of what has happened, the non OMC-Mercury players have not been held down by plaintiff lawyers and forced to testify “Guards don’t work” before they let them up for air. Even still, some of them have publicly spoken out against propeller guards:

- Volvo Penta via William E. Perry, Director of Consumer Affairs 2 November 1995 letter to USCG in response to request for public comment on CGD95-041 (now filed as comment 1909 on USCG-2001-10299)

- Volvo Penta via William Calore, General Counsel 29 August 1996 letter to USCG in response to request for public comment on March 26,1996 Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking as comment #63. It is now filed as comment # 2025 in USCG-2001-10299. The document also includes their response to the Shirley Koop / Jones houseboat propeller accident.

- Honda via William R. Willen, Managing Counsel, Product Regulatory Office March 11, 2002 letter to USCG in response for public comment on USCG-2001-10163 (the houseboat proposal). They objected to the proposal on several counts including, “A design that could prevent any injury would result in a loss of propeller function.” Honda also objected because propeller guards were not defined and due to the lack of standards for interlocks and other devices.

- In response to 2012 interrogatories in Coxe v. Yamaha, Yamaha U.S. denied they knew an outboard propeller presented a significant injury and death hazard to persons and marine life, they denied that from time to time outboard motors come in contact with persons in the water, they denied that from time to time operators are thrown overboard by various forces, and they denied that operators that had been thrown overboard may be struck by propellers

As a result, any pressure to develop a guard or to debunk existing guards has primarily been placed on Brunswick / Mercury Marine, and Outboard Marine Corporation / OMC.

However, we did see Yamaha UK run and hide in late 2012 when we pointed out their comments about a prop guard they were reselling as part of a rescue outboard motor package were in opposition to longstanding industry positions against propeller guards.

Brunswick / Mercury Marine Propeller Guard Development Efforts

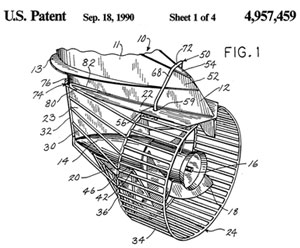

As with OMC, Brunswick pretty much claims “people protecting” propeller guards do not exist. Their one propeller guard development project resulted in what we call the Snyder Guard. This 1989 project was being developed at the same time as USCG’s 1989 National Boating Safety Advisory Council (NBSAC) subcommittee on propeller guards was developing their report.The Snyder guard was developed for a military application of soldiers being in shallow water loading and boarding a boat with the engine running needing protection for their feet. While the military documents appear to show the military’s intent for the guard to provide protection at all times, Mercury had the contract amended to read that guard only provided protection when at rest or moving very slowly, and the guard could be a hazard at higher speeds.

Mercury even added this specific disclaimer: “This device is not intended to and will not prevent very serious or fatal injury when used in other foreseeable applications, and care should be taken to see that this device is not placed in general use.”

A patent application was filed focusing on the method the guard used to attach to the drive. The patent made no statements as to the purpose of the guard or any safety it may have provided.

Mercury and OMC actually joined together in late 1990 to test the Snyder guard on an OMC outboard in the large circular tank at State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo. Many documents came from that research all showing the guard did not protect people when the drive was moving more that just a few miles per hour. While there are plenty of arguments about how that testing was conducted and some of the devices used, the industry came away saying the guard did not work. That SUNY test cost approximately $300,000 (per Dick Snyder in Ard v. Brunswick) and was split between OMC and Mercury. Billings for the testing were handled by a bevy of lawyers.The remainder of Mercury’s expenses related to propeller guards have been spent in conducting tests devised by Dick Snyder, or in litigation testing of propeller guards proposed by others (debunking propeller guards). Before someone jumps on my use of “debunking” there is nothing wrong with Mercury debunking propeller guards that do not work. The problem is when Mercury constructs special situations designed to make the guard fail, then make no efforts to “fix” the guard, even when the “fix” is extremely obvious to them (PropBuddy and trim limit spacers), or when they objected to the test when their own Synder guard was being tested by the military (being trimmed full under), or when they could not think of anyway to improve reverse with the 3P0 guard when the rear screen was partially blocked by a giant logo.

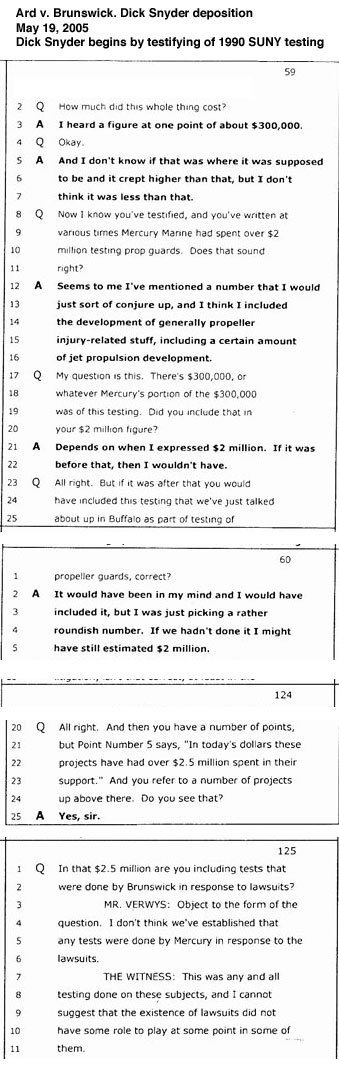

At any rate, in Ard v. Brunswick in May 2005 (Circuit Court of Jackson County Missouri at Kansas City) Mercury addressed their propeller guard expenses in several statements. The basic answers provided by Dick Snyder, Mercury Marine long time propeller accident expert witness, was they spent about $2.5 million in today’s dollars (2005) to test other people’s propeller guards and to develop water jets. He noted some of that testing was the result of lawsuits.

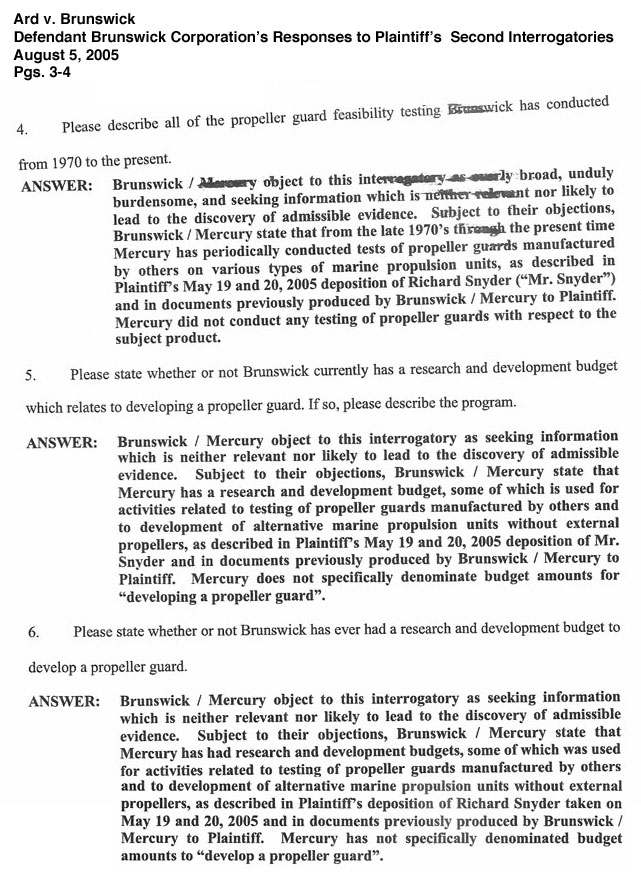

Brunswick Corporation went on to respond to the Plaintiff’s Second Interrogatories in the same case (Ard v. Brunswick) in which they say they tested guards built by others, developed alternative marine propulsion units without external propellers (water jets), and had no line item in their research budget for developing propeller guards. Brunswick’s actual responses are shown below.

In summary, Brunswick/Mercury Marine tests guards built by others (sometimes related to legal cases), developed and patented the Snyder guard for a very special military situation then discredited it in the SUNY testing, had no line item in its research budget for developing propeller guards, but has spent approximately $2.5 million in today’s dollars (2005 dollars) to test propeller guards and develop water jets since the beginning of Brunswick.

Although they never come out and directly say it, it seems as if Brunswick is trying to say they never spent a penny on trying to develop a “people protecting” propeller guard of their own for general use.

Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) Propeller Guard Development Efforts

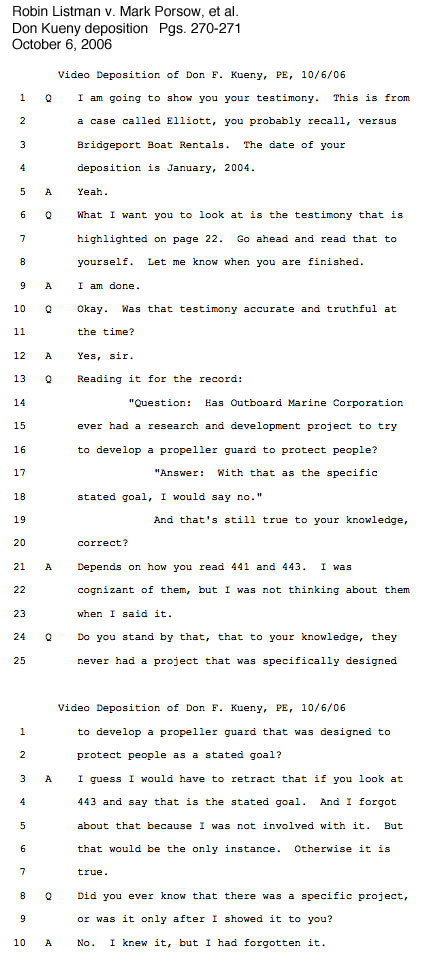

Don Kueny started with Outboard Marine Corporation as a research engineer straight out of school about 1957. He became a Project Engineer in outboards about 1969, Chief Engineer for Outboard Design in 1975, and Senior Chief Engineer for all Corporate Products in 1991. Don Kueny retired in 1993 and has continued to serve as an industry consultant and expert witness after OMC’s bankruptcy in late 2001.

In Robin Listman v. Mark Porsow,, et al., Mr Kueny was deposed regarding any potential liability of OMC in the case as their outboard was on the boat. The case was in the Second Judicial District Court of the State of Nevada in and for the County of Washoe.

In Mr. Kueny’s October 6, 2006 video deposition (Listman v. Porsow), Mr. Kueny was shown his January 2004 deposition in the Elliot case in which Mr. Kueny was asked if Outboard Marine Corporation ever had a research and development program to develop a propeller guard to protect people, and had answered no.

But in this deposition (Listman v. Porsow), Kueny said when he made that statement earlier, he had forgotten about Project 443 which he thinks may have had that as a stated goal.

OMC Project 443 was initiated in January 1980 with the final report issued May 11, 1981.

The Objective as stated on the report (Report No. 443-1): “To determine if the performance of an outboard motor used for water skiing would be unduly comprised by a guard which gives a high degree of protection from personal contact with the propeller.”

Summary of results: “The guard designed to achieve the objective caused a loss of performance and efficiency. Also the design was structurally deficient. The experimental model failed even though not exposed to abnormal service or tests.”

OMC used a rubber foot to check the protection the propeller guard provided. The project resulted in U.S. Patent 4,304,558, but OMC later tried to discredit the device

OMC basically ran some vanes extending along side the gearcase from the front, connected them to a wide ring surrounding the propeller, and used a rear cover with several vanes radiating from the hub area with an annular recess (circle) in the middle where the exhaust comes through. It also tried to conduct exhaust gasses to the rear edges of the shroud reduce drag.

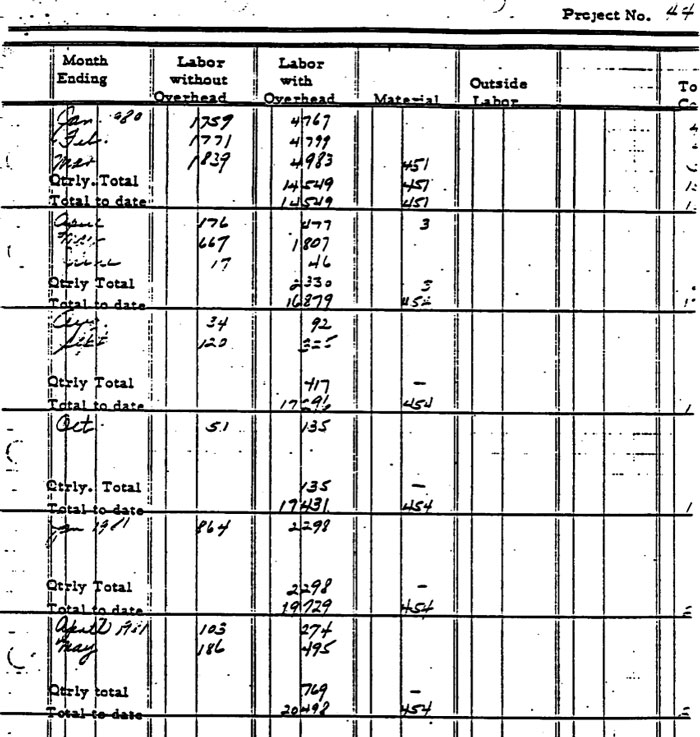

OMC’s actual test request lists their quarterly cost thru May 1981 and sums them up as $20,498 for Labor with Overhead plus $454 for materials.

Thus, the one project research project OMC claims was for developing a “people protecting” propeller guard has a total cost of $20,952.

Ted Holterman was the principal research engineer at OMC in 1991 and is listed as the inventor on U.S. Patent 4,304,558 that resulted from OMC project 443. The patent says the invention is for improving thrust and protecting the propeller from underwater obstructions. Its says nothing about people safety issues.

In Ted Holterman’s 1991 deposition in Eggen v. OMC (pgs. 40-41), Holterman says he knows of no OMC projects to develop a guard to sell to the public. When asked about his U.S. Patent 4,304,558 that resulted from OMC Project 443, he said “That guard was not intended as a people-protection guard.” When cornered with the coversheet of Project 443 that said it was to investigate methods to reduce the possibility of injury by the propeller with minimal loss of performance, Holterman answered, “That’s what the cover sheet says.”

On pages 50-51 of the same Eggen v OMC deposition, Holterman said the OMC Project 443 guard broke in a matter of minutes during the static thrust test. When asked what it would have taken to have made it stronger, he said they could have used steel instead of aluminum in its construction. However, the project was closed before any solutions were attempted. He failed to mention some of the components could be made thinner (reducing drag) while still being stronger if made from steel.

At any rate, when OMC claims Project 443 as a people protecting guard, their total expenses to develop people protecting propeller guard in their 70 plus years of existence were about $21,000. When they do not claim it, their total expenses to develop people protecting propeller guards were zero.

Total Expenses by Brunswick / Mercury Marine and Outboard Marine Corporation OMC to Develop People Protecting Propeller Guards for General Use

Brunswick / Mercury Marine had the Snyder guard project for protecting the feet of soldiers loading small boats with the propeller still running. They state the guard was not for general use and together with OMC showed it caused significant injuries itself during the 1990 SUNY testing.

Outboard Marine Corporation / OMC had OMC Project 443 that some of their experts want to count as a people protecting propeller guard project some of the time. Project 443 cost $20,952.

Therefore, Brunswick / Mercury Marine and Outboard Marine Corporation / OMC together state they spent the sum total of zero or $20,952 on developing people protecting propeller guards depending upon who and when you ask the question to OMC expert witnesses.

While these numbers are a little old, OMC was bankrupt by the time their data was provided so they obviously did not continue to develop people protecting guards. We know of no project to develop people protecting propeller guards at Brunswick Corporation / Mercury Marine since the 1989 Snyder guard and would not expect to find one as they are regularly asked that question in court, plus their continued statements about propeller guards lead us to believe they have no plans to do so.

However, both firms have spent significant sums in testing propeller guards built by others and admit at least some of those tests were performed as the result of litigation.

Why Didn’t They Spend More to Develop A People Protecting Propeller Guard?

OMC and Brunswick each had annual sales in the few billion dollar range. For them to have spent less than $25,000 combined over the last several decades to develop a people protecting propeller guard sends a clear message. Either they truly feel such a project is impossible, or they do not want a people protecting propeller guard to exist.

Many propeller safety advocates suggest it it the latter. The industry does not want people protecting propeller guards to exist because the industry:

- Would have to explain why propeller guards do not work in other similar applications if they ever accept them for one application (such as rental houseboats)

- Would have to explain why they did not develop propeller guards earlier

- Would have to pay to retrofit propeller guards to thousands to millions of boats in the field, or explain why they will not retrofit them

- Would have to eat crow for stating people protecting propeller guards were impossible for decades

- Lose millions of dollars in sales of new propellers that will no longer be purchased to replace dented propellers because they were protected by prop guards

- Some people will continued to be injured or injured less severely, the industry would continue to be sued even if guards were ubiquitous

Mercury Marine’s continued litigation testing of propeller guards also suggests they do not want one to exist.

prop guards are simple, STAY AWAY FROM ROTATING PROPS, would you walk into or near a rotating airplane prop? i didnt think so. why would you get in the water near a rotating boat prop. use common sense and conduct yourself in a safe manner.

It is not possible to avoid rotating propellers in all situations unless you stay off the water and away from the beach.

We note some people are:

1. Ejected from a boat that is now unmanned and circling in the Circle of Death

2. Swimming behind a houseboat in which the engine is not running, but someone quickly starts it and reverses the houseboat

3. Fall while tubing or water skiing and are struck by the boat’s propeller when it comes back to pick them up

4. Swimming in a properly marked swimming zone but a boat passes through and strikes them with the propeller

5. Diving under a diving flag, surface and are struck by the propeller of a passing boat.

It is not possible for everybody to stay away from rotating propellers in all situations with boats as they exist today. Please note we do not recommend propeller guards be put on all vessels. See our Position Statement on Propeller Guards. We also note boating safety practices can prevent some of the accident scenarios listed above, but that has been true now for about a hundred years and they keep happening.