Are Propeller Guard Technologies Being Suppressed by the Boating Industry, Along With Other Propeller Safety Devices?

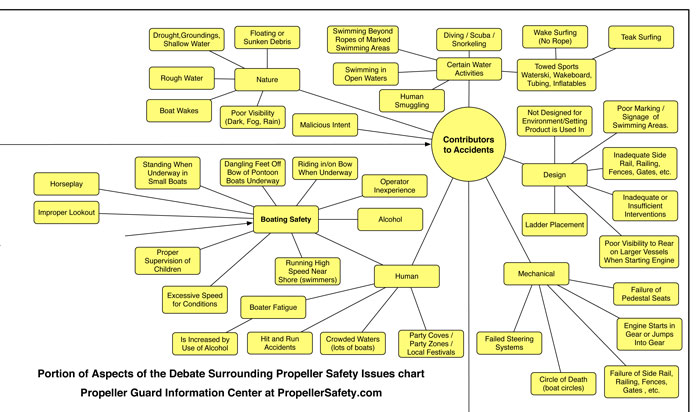

Many have accused the boating industry of suppressing the development and deployment of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

A list of ways in which the boating industry has been accused of suppressing propeller guard inventions, technologies and other propeller safety technologies is provided below. They are grouped by events or topics and partially organized by timeline.

Please Note

We try to keep the Propeller Guard Information Center / PropellerSafety.com fair and objective on propeller safety issues. However, as is often the case in discussing the suppression of other technologies, this list includes several unproven accusations and claims made by others. We are not saying we believe every single one of these points or that every one of them is true. Several of these points are based on circumstantial or hearsay evidence. You will need to make your own judgement call as to the truthfulness of these statements.

Many of these accusations have been made previously. Those with experience in this field may harbor emotional feelings for or against several of the points made here. To our knowledge this is the first large scale collection of these claims.

For those who feel many of the points made here are untrue, we remind you that for the boating industry to have suppressed propeller safety inventions and technologies ONLY 1 of these over 140 points needs to be true. For the industry to have willfully suppressed propeller guard and other propeller safety technologies you will need to decide how many of them are true and if in your opinion those particular points create the preponderance of evidence necessary to indicate willful intent.

Many of our comments about slowing further development of these technologies hinge on the industry not using the products. If the boating industry began to apply almost any of these technologies, even in a limited way, inventors and designers would begin to make further improvements upon them.

Ways the boating industry has been accused of suppressing development and deployment of propeller guards and other propeller safety inventions and devices:

Table of Contents

- Federal Boating Safety Act (FBSA) of 1971 – Federal Preemption

- Kill Switches / Lanyards

- 1989 USCG National Boating Safety Advisory Council Propeller Guard Subcommittee

- 1990 SUNY Testing

- USCG Solicited Houseboat and Displacement Recreational Vessel Propeller Accident Comments USCG-01-10299

- Recreational Boating Safety Congressional Hearing (107-20) May 15, 2001

- Houseboat Propeller Injury Mitigation Regulation USCG-2001-10163

- Propeller Guard Test Protocol

- Event 1 Propeller Accident Statistics Problem

- More Propeller Accident Statistics Issues

- Boat Design

- No Response / No Action

- The Courtroom

- Boating Industry Laughs and Jokes During Propeller Guard Impact Tests Behind Closed Doors

- Pulls Back Any Internal Development

- The Public Debate

- Industry Attitude

- Education is the Only Answer

- Thwart the Efforts Propeller Guard and Propeller Safety Device Inventors and Device Builders

- The Paradox

- Follow the Money

- Propeller Guard Manufacturing Challenges

- Miscellaneous

In Defense of the Boating Industry

Federal Boating Safety Act (FBSA) of 1971 – Federal Preemption

A major update of Federal boating laws occurred in 1971. It was known as the Federal Boating Safety Act of 1971. It did not require the use of propeller guards.

- Propeller guards not required on all boats. USCG did not say propeller guards would be required on all boats in the 1971 Federal Boating Safety Act. The boating industry later interpreted that as propeller guards could not be required on any boat. The industry did that by saying Federal laws preempt state laws (commonly known as Federal Preemption). So, if the Feds say prop guards were not required on all boats, states could not require propeller guards on any boats. By making this claim (Federal Preemption), the industry was able to slow the further development of propeller guards.

- Settled Lewis, Deceased v. Brunswick. In 1993, Kathy Lewis, an Oklahoma teenager on vacation in Georgia, fell overboard, was repeatedly struck by the boat propeller, and died from her injuries. Her parents sued Brunswick. The case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court in early 1998. The Supreme Court heard the case, Brunswick presented their Federal Preemption defense, and the court was writing their opinion. Brunswick settled the case for a reported $700,000 before the Supreme Court delivered its opinion. Brunswick was afraid they were going to loose their Federal Preemption get out of jail free card, so they settled. In effect they were paying $700,000 to buy as many more years of the Federal Preemption defense as they could until another propeller case worked its way to the Supreme Court. By settling, Brunswick kept the preemption defense and the propeller guard industry was kept from developing further.

Unusual Settlement Removes Third Case. Washington Post. May 26, 1998.

“For Brunswick, the settlement offer was a way to try to head off a ruling against the company that could influence other cases, which had been going their way. Until the time of oral arguments, the company had made no serious efforts to settle.

Kenneth S. Geller, a leading appellate lawyer hired by Brunswick to make its case at the high court, said the manufacturer’s position was “strong.” But he acknowledged the risk of an adverse national policy.

“Brunswick didn’t take this case to the Supreme Court,” he said, referring to the fact that the court had granted the Lewises’ appeal. “It had won almost all of these [propeller guard] cases in lower courts. So Brunswick was delighted to maintain the status quo.”

Other propeller injury cases are in lower courts, but it is likely to be a few years before another reaches the justices.

Neither Geller, Hudson nor the immediate parties involved would disclose the settlement amount. But two other people who were close to the negotiations estimated Brunswick paid out about $700,000, which for Vicki and Gary Lewis (a homemaker and truck driver) was significant money”.

- Lost Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine in the U.S. Supreme Court in December 2002. The Federal Preemption defense worked great for the industry from the early to mid 1990’s to December 2002 when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Federal Preemption as a defense in propeller injury cases in Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine. The U.S. Supreme Court said that neither the text nor the intent of FBSA 1971 prevents common law claims concerning the guarding of propellers. From the mid 1990’s to December 2002 the industry defeated numerous propeller lawsuits with their preemption defense which was later struck down by the Supreme Court. By relying on a defense that was later struck down, the industry delayed the advancement of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices. If all those propeller cases that were quickly dismissed based on Federal Preemption had been tried based on their merits, things would be vastly different today for many propeller guard and propeller safety device inventors and manufacturers.

- Kill Switches. The industry fought kill switches (emergency engine cut-off switches) from the mid 1970’s when they were first introduced for recreational boat applications. Now over 3 decades later kill switches are still not standard equipment on all small boats. We suspect the industry’s resistance comes from three objections: (1) Keep costs down, (2) Prevent being sued for not having them earlier, (3) Desire to keep boating as carefree as possible so more people will boat.

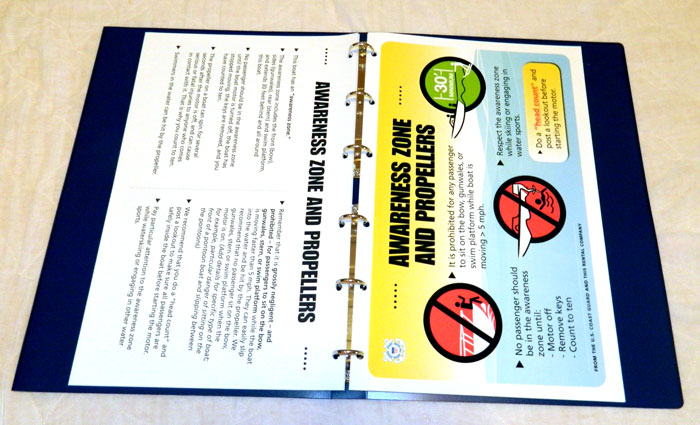

Just last year (2011) the U.S. Coast Guard circulated a proposed rule for public comment on installing kill switches and separately on making their use mandatory when a kill switch has been installed in the vessel. The industry has yet to fully embrace even just the installation of kill switches on all small boats. By continuing to resist this development the boating industry has slowed the acceptance of kill switches, a propeller safety device that prevents unmanned boats from circling and striking those who fell overboard.

- By resisting kill switches from the beginning and still not requiring installation of lanyard kill switches, the industry has slowed the development of sensor based kill switches. By refusing to make kill switches standard equipment on all small boats, the industry has slowed the development of virtual lanyard kill switches like MariTech’s Virtual Lifeline and Autotether.

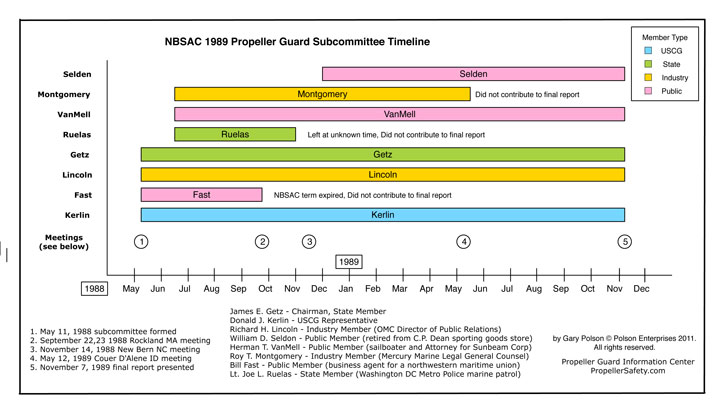

- The 1989 National Boating Safety Advisory Council (NBSAC) Subcommittee on Propeller Guards report, still touted in court by the boating industry as a reason not to use propeller guards, was put together by a committee stuffed full of powerful industry representatives including Mercury Marine’s General Council (Roy Montgomery), Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC)’s Director of Public Relations (Dick Lincoln) and was chaired by James Getz who went on to be the leading expert witnesses for the defense as soon as the final report was published. Many of the meetings were attended by Dick Snyder, Mercury Marine’s expert witness in propeller guard cases. Several members came and went including one that was later indited for mail fraud with 16 other union members for embezzlement and fixing a union election during the time he served on the committee.

Robert Taylor made presentations to the subcommittee and his work was included as an appendix in the final report. Robert Taylor also went on to be a leading expert witness for the defense as soon as the final report was presented.

The Propeller Guard Subcommittee’s final report found no universally applicable propeller guard and failed to note some guards work in certain applications. Mr. Getz, chairman and compiler of the final document said it was sent to the other subcommittee members at that time for corrections, but none were made (kind of hard to believe several people would not find anything to comment about in a large emotional charged report). Mr. Getz signed the report and said it was unanimously adopted by the other members, but their names were only typed. This document single-handedly held propeller guards at bay until the Federal Preemption defense and is now once again being used in the courtroom.

- Roy Montgomery was removed to safe face. Jim Getz himself has testified in court that he asked for Roy Montgomery, General Counsel for Mercury Marine, to be removed from the subcommittee before the final report was published so his name would not taint the purported independence of their findings. These kinds of actions show how propeller guard inventors and manufacturers were railroaded by the 1989 NBSAC subcommittee on Propeller Guards.

- Pick and Chose Which Parts of 1989 NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee Findings to Apply – Vivid Depictions. The boating industry holds the 1989 study in high acclaim and frequently cites its finding “The U.S. Coast Guard should take no regulatory action to require propeller guards.” However when the U.S. Coast Guard brought out the “Don’t Wreck Your Summer” public service announcement video featuring a propeller accident in late 2010, the industry was successful in banning the video because it very vividly depicted a propeller accident and as such it showed the boating industry in a bad light (showed their products hacking up people). However, the same 1989 NBSAC study the industry touts found the Coast Guard should include the potential hazards of negligent boat operation in educational and awareness campaigns. More specifically, such programs should “be as vivid as possible in depicting underwater impact scenarios.” By failing to adhere to the very study they hold in high acclaim, the industry impacted the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices by hiding the need for them.

- Pick and Chose Which Parts of 1989 NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee Findings to Apply – Statistics – The boating industry holds the 1989 study in high acclaim and frequently cites its finding “The U.S. Coast Guard should take no regulatory action to require propeller guards.” However the same study recommends the Coast Guard “develop a complete and comprehensive data base on underwater accidents.” “This should involve, as an integral part, U.S. Coast Guard involvement in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS)…”. Now twenty plus years later propeller strike statistics are minimally more complete and USCG has yet to fully participate in NEISS. By failing to record propeller accidents, the need for propeller guards and other propeller safety devices was hidden from view and their development was stalled.

- The 1989 NBSAC study did not acknowledge any sensor based devices. Sensor based devices had been proposed earlier, yet NBSAC 1989 totally ignored that approach. By failing to recognize their existence, virtual propeller guards, ladder switches, gate switches, virtual lifelines, Autotether, and similar devices were postponed from development at that time.

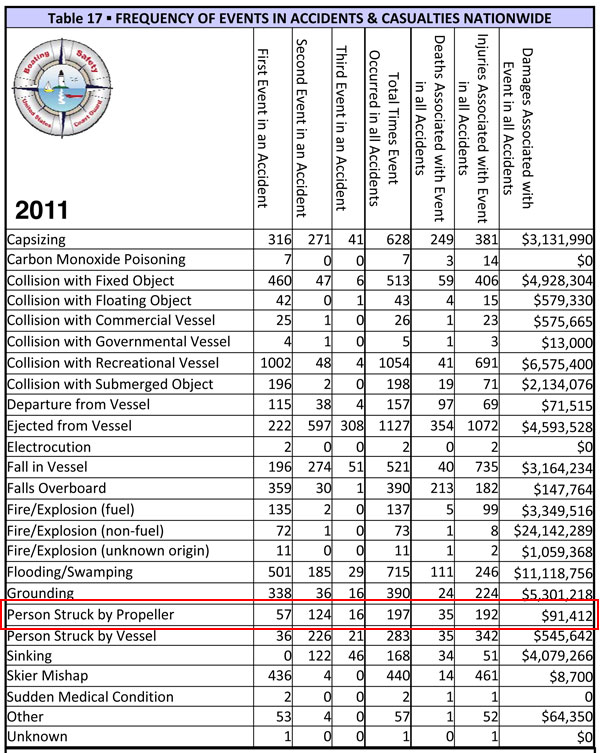

- Tried to mislead Getz with Event 1 statistics – The Coast Guard reports accidents as a sequence of events (like Event 1 = collided with floating object, Event 2 = fell overboard, Event 3 = struck by propeller). Dick Snyder’s 22 September 1988 presentation to the subcommittee and his 6 October 1988 follow up letter to Getz provided propeller strike statistics. However, in his presentation and in his letter, Snyder provided Event 1 statistics and presented them as representing the total number of propeller accidents, injuries, and fatalities. In reality they only represented a small fraction of those reported to the Coast Guard. Thus only a fraction of the injury and fatality data was presented which played down the need for propeller guards. This prejudiced the subcommittee (not many accidents, this is not a big problem). Eventually, Dick. Snyder, the industry’s leading expert, wrote Jim Getz (February 23, 1989) of his “discovery” that USCG reports accidents as a series of events and he provided new data based on all three events. However, as seen in the timeline on our coverage of the subcommittee, the subcommittee had already met for three of its four meetings before presenting their results, and some members were already gone from the roster. We see no records of Getz sharing this information with the rest of the Subcommittee AND Snyder’s newly found statistics are not in the final report. By feeding the Subcommittee low-ball statistics, the needs for guards was masked and their further development and deployment was delayed.

- Final report contains no statistics for annual propeller strikes. Getz talks in general about propeller accident statistics and some of the problems in obtaining accurate ones, but provides absolutely no data on the number of propeller accidents, injuries, or fatalities. The only number Getz cites is for 1982 from Robert Tyler’s presentation (7 year old data). He says that in 1982 for open motorboats from 14 feet to 18 feet in length, that 4.9 percent of the fatalities resulted from being struck by a propeller but Getz does not tell you how many fatalities there were (see pgs. 7-10 of the final report). Absolutely no numbers are provided for the number of accidents or injuries. Its hard to believe the final report provides no statistics. How could they evaluate the need for solutions if they did not know how big the problem was? Robert Taylor’s appendix does provide some numbers for propeller fatalities but all it provides for injuries is “injuries related to propellers while boating or water-skiing are approximately on-half of one percent of this risk of injury while boating or water-skiing.” He makes no comments as to their relative severity. The study avoided statistics to condemn propeller guards and slow their future development and deployment.

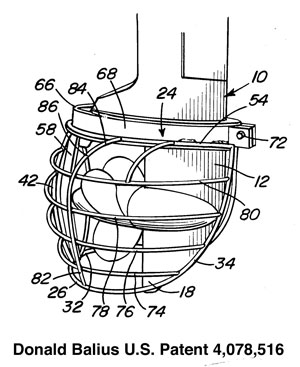

- Exaggerate the increased cross sectional area of propeller guards relative the the cross sectional area of an open propeller. A 1979 USCG study, Struck by Propeller, by USCG’s own Al Marmo found propeller guards could be useful in preventing propeller accidents and mitigating the resulting injuries. Dick Snyder at Mercury Marine quickly took to trying to convince Mr. Marmo of the errors of his ways. One of Mr. Snyder’s efforts to do such was a December 15, 1980 letter to Mr. Marmo summarizing Mercury’s on water testing of the Balius (large bulbous “basket like” cage) and Williams (ring) guards. Mr. Snyder discusses blunt trauma issues associated with the increased cross sectional area of a guard vs. the propeller, then on page 3 of his letter Dick Snyder makes the following calculations based upon the very large “basket like” Balius guard. Mercury was testing with a 13.5 inch diameter propeller. Propeller area = 143 sq.in less the 24 sq.in. already covered by the gearcase = 119 sq.in. The large Balius basket was about 20 inches wide X 18 inches tall for a total of about 360 in.sq. Mr. Snyder says the guard has over 2.5 times the frontal area of the propeller (and he conveniently never subtracted the frontal area of the drive from that of the guard). But more importantly, he selected a propeller guard style (the Balius basket guard) with the one of largest relative diameters to the propeller diameter ever built for use in his comparison. Anybody find it interesting he did not use the Williams ring guard he was also reporting test results from to Mr. Marmo for his comparison? A ring guard would have probably been in the range of 15 inches in diameter with an area ratio of (15 X 15) / (13.5 X 13.5 ) = 1.25 The outrageous ratio (guards have over 2.5 times the frontal area of a propeller) quoted by Mr. Snyder became even further embellished almost a decade later (see next item below).

- Object to propeller guards based on their increased cross sectional area that could strike victims and create blunt trauma issues. This oft raised objection was a strong piece of the 1989 subcommittee’s findings. They found “that the frontal impact area would be increased by three times by attaching a guard.” (see pages 13-14 of the 1989 study). Wherever they got three times from fails to note to leading edge of the drive and the anticavitation plate already impact some portion of this increased area, but the calculation itself is hard to believe. A 14 inch propeller has a cross sectional area of about 154 square inches. For a guard to have an area three times that size, it would have to be about 24 inches in diameter. The idea that a guard needs 5 inches of prop tip clearance is ridiculous. Ridiculous or not, they used it to exaggerate the potential of a victim to miss the propeller but be struck by the guard and were able to say guards are more dangerous than any benefits they may have. Thus the industry postponed any further development of propeller guards at that time.

2 December 2012 Update – I found the source of these calculations. A December 15, 1980 letter from Dick Snyder (Mercury Marine) it is further discussed in the item above this one. As mentioned above, it is interesting that the outrageous 2.5 ratio quoted by Mr. Snyder in 1980 became even further embellished to a ratio in excess of 3.0 by 1989. To our knowledge, no on else has ever called their bluff on these outlandish statements, but the Coast Guard did act upon them. Or more accurately, the Coast Guard failed to act based upon them, USCG at least twice decided not to encourage the use of guards based upon those statements. - Reject guards based on cross sectional area but do not rejects boats for the same reason. As mentioned above, the industry rejected propeller guards in part due to their increased cross sectional area and the potential for blunt trauma when someone is struck by a propeller guard. The subcommittee failed to note boats have a much larger cross sectional area than propeller guards and thus create a far greater hazard blunt trauma hazard than propeller guards. Rejecting propeller guards when boats and drives create a far bigger hazard was not fair to inventors and manufacturers of propeller guards. By rejecting guards, the industry delayed their further development.

- Fails to mention the “Circle of Death”. The final report fails to mention that often, the only person on board a small boat is the operator. They can be ejected by striking a wave, falling overboard, etc. while the boat is underway. In that situation, the boat often begins to circle and the operator is repeatedly struck by the boat and or the propeller (called the Circle of Death). Unmanned boats in the Circle of Death are often circling so tightly quickly their top speed is quite slow. Propeller guards could provide excellent protection in some of these situations. The Subcommittee failed to recognize that, and delayed the further development of propeller guards.

- Went from no findings to major findings months after the last subcommittee meeting. In an interview published in the St. Petersburg Times (Florida) on September 4, 1989, Jim Getz said the subcommittee had not found anything alarming one way or the other (towards the use of guards). The subcommittee was not expected to make any major recommendations about guards. Gets said, “I’ll be honest, when we make a report, we’ll be making a judgement call.” As can be seen from the Subcommittee timeline chart above, their last meeting was on over six months before the interview (last meeting was May 12, 1989). Since that final meeting the subcommittee members had been compiling their thoughts and Getz had been writing the final report which was to be delivered approximately two months after this interview. If Getz is telling the truth, somehow in that final two months (after the other subcommittee members had already supplied their findings to him) the subcommittee went from it being a very close judgement call to their often quoted number 1 finding:

“The U.S. Coast Guard should take no regulatory action to require propeller guards.”

and backed it up with statements like this one from page 24 of the subcommittee’s final report:

“Although the controversy which currently surrounds the issue of propeller guarding is, by its very nature, highly emotional and has attracted a great deal of publicity, there are no indications that there is a generic or universal solution currently available or foreseeable in the future. The boating public must not be misled into thinking there is a “safe” device which would eliminate or significantly reduce such injuries or fatalities.”

Either Getz was lying in the interview, he was misquoted/misunderstood in the interview, or something happened after this interview which was already 6 months after the last subcommittee meeting and after he received the materials from his fellow subcommittee members that does not appear in their records that swung them strongly against the use of propeller guards. Some will say that it was the maturing of a deal with the industry to take the subcommittee’s final report on the road and use it as their leading expert witness. Whatever happened, it set back the development of propeller guards. Please note an optional subcommittee finding could have been, we are not sure, the evidence is inconclusive, we ask USCG conduct some unbiased testing of various propeller guards on boats and applications thought to have high risk of propeller strikes, and we will base our recommendations based on the results of that testing in conjunction with our previous findings.

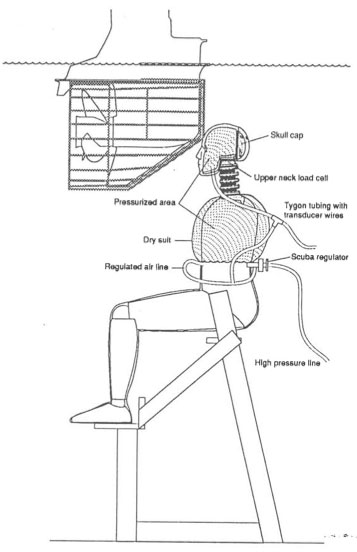

- 1990 SUNY testing was under the direction of industry legal departments. The tests were setup and and paid for by OMC and Mercury Marine’s legal departments, not by their engineering departments. Had their engineering departments been tasked with trying to create a functional guard, those tests could have significantly advanced the development of propeller guards. Instead they slowed the development of propeller guards by generating legal evidence for why guards do not work which has since been broadly cited.

- SUNY test was designed to fail the propeller guards. The test was constructed to show the guards failing. For example, they used the Snyder guard that closely follows the contour of the drive. They had it strike submerged dummies in chairs in the forehead. They hit their foreheads with the portion of the guard where the drive bends back below the torpedo to the skeg (the “point” of the guard). By showing the damage this could cause to a “victim” they delayed the development of propeller guards.

- 1990 SUNY testing crew was expressly forbidden to run any tests with an open propeller. The boating industry did not want any comparisons to be able to be made between the respective injuries (injured by guard vs. injured by propeller). Imagine a video of an open propeller striking a dummy in the head. By not allowing open propellers to be tested, the industry was able to say guards are bad without having to say guards may cause injuries, but they are safer than open propellers. The lack of comparison allowed the industry to delay the further development of propeller guards by just saying they were bad.

- Stiff Necked Dummies Don Kueny (OMC) later admitted they knew the springs in the dummy’s necks were four to five times stiffer than a human neck. (See the Decker v. OMC transcript about page 876.)

USCG Solicited Houseboat and Displacement Recreational Vessel Propeller Accident Comments CGD-95-041 / USCG-01-10299 notice May 1995 & USCG Solicited Rental Boat Propeller Injury Comments CGD-95-041 notice April 1997

In response to several high profile rental houseboat propeller and pontoon boat accidents, propeller safety advocates, and some legal cases, the Coast Guard once again put out a request for public comment on propeller guards on rental boats and displacement boats.

- Tried to position USCG’s request for comments as a response to a single individual (Marion Irving deCruz that lost her son in a houseboat accident) and tried to discredit her deceased son. Several entities tried to position the current concern for propeller safety as the response to a single accident (Cruz) and tried to discredit his actions and him personally (example comments: Dick Snyder / Mercury Marine comment 46, US Marine comment 635, Volvo Penta comment 1099, Hulsizer comment 1982, Harborside Marina comment 2003, Volvo Penta comment 2025 (also discredits Shirley Koop Jones)). By trying to claim all the noise resulted from one lady bugging the Coast Guard, and by discrediting her deceased son, they were able to defeat the movement at that time which delayed the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- Heard and nothing happened. NBSAC (USCG’s National Boating Safety Advisory Council) passed a resolution recommending measures to reduce propeller accidents in April 2001. Several propeller safety advocates spoke, were present, or supplied materials to the May 2001 Congressional Hearing: Marion Irving de Cruz (SPIN), Phyllis Koptyko (SPIN), Jon Vernick (Johns Hopkins University and the Institute of Injury Reduction), Keith Jackson (MariTech), Lowell Wiecker (former Governor of Connecticut whose son was nearly killed by a prop), Rob Simmons of Connecticut (a constituent of his was injured). Congress asked Admiral Cross (USCG) if they were going to implement the NBSAC measures. Admiral Cross said USCG was already putting together a regulatory work plan. Admiral Cross continued, “we’re absolutely taking it very seriously, and we’re moving forward through the process with that recommendation.” Propeller injuries and fatalities were a major topic of the hearing. Congress left thinking the problem was going to be addressed. Not one single representative of the boating industry spoke out against the NBSAC recommendations during the hearing. The industry just kept quiet and then later opposed every USCG propeller safety proposal based on the NBSAC recommendations. The industry successfully defeated the proposals, and nothing has changed. As a result of the industry laying low in the Congressional Hearing, they escaped direct Congressional propeller safety regulations. By being quiet and later defeating all the proposals, they made it difficult for manufacturers of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices to market and further develop their products.

- Inflated the estimated cost of propeller safety devices in the Proposed Houseboat Propeller Safety Regulation. In our 2010 study on the rejection of a proposed houseboat propeller safety regulation, we point out the National Marine Manufacturers Association (NMMA) in conjunction with the Houseboat Industry Association (HIA) estimated the cost of implementing the proposed rule at $3,303.70 per houseboat (pg. 83 of our study) while we proved implementation cost was actually $196.34 (pg. 29 of our study). The difference was due to several huge errors made by the boating industry in their calculations. By exaggerating cost of implementation, the industry effectively limited the further development of propeller safety devices.

- Misled the Coast Guard in the Proposed Houseboat Propeller Safety Regulation. The boating industry’s cost estimate and a letter in their behalf from the Small Business Administration, led the Coast Guard to believe implementation costs were much higher than they actually were. The SBA told the Coast Guard the proposed regulation would be a burden on small business, but the SBA letter included at least 15 major errors including using the wrong data set. Together, they were able to block the proposed regulation and effectively block the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices (ladder switches).

- Tried to use the lack of a definition of the word “Houseboat” as a reason to block the Proposed Houseboat Propeller Safety Regulation (pg 38 of our study). While a definition would be needed, the industry just used it as a means to reject the regulation which slowed the further development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- Categorized accidents into infinitesimally small groups. For example, they broke houseboat propeller accidents into rental and nonrental accidents (note there are only about 5,000 rental houseboats in existence) by year, then into annual subgroups based on drive type (inboard, outboard, inboard/outboard) and by severity (injury or fatality). Then by discussing the small numbers in the resulting matrix cells, the industry gave readers the idea few accidents were involved. For example, they discussed the cell/data for 1991-1995 inboard rental houseboat fatalities with a zero in it. As a result, no action was taken and the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices was delayed.

- Failed to find unreported and miscategorized propeller accidents. The industry did not even look for houseboat propeller accidents that might not have been reported to BARD or might have been put in the wrong category in BARD. We identified several of them. The number of injuries and fatalities was used in the economic justification calculations. By leaving them out, the rule appeared unjustified. When in fact it was. Thus further development of propeller guards and propeller safety devices was delayed.

- Failed to find the Falvey accident. Among the accidents the industry failed to find was the Falvey accident. A lady and her husband were part of a floatilla of rental houseboats touring Lake Mead with several government agencies onboard (National Park Service, U.S. Forestry Service, and the Bureau of Land Management). The lady was struck by the propeller. She and her husband later supplied public comments about their accident to a USCG request for public comment AND they both made a presentation to a NBSAC Meeting about her accident which was attended by several industry executives. Still the industry somehow ignored the accident and did not include it in their calculations. By doing so (and excluding several other accidents as well) they tried to show the proposal was not economically justified. Thus, once again propeller guards and other propeller safety devices missed an opportunity for further development.

- Rallied the troops. Acting through NMMA the boating industry rallied the troops to come out fighting against USCG-10163. NMMA put out two warning letters to members including a suggested format for their public comments to be sent to USCG. NMMA and HIA (Houseboat Industry Association) responded in conjunction with the U.S. Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy. By rallying the troops the industry was able to defeat the proposed regulation and delay the deployment of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- Vanishing pontoon boats. Pontoon boats were in the earlier 10299 proposal (displacement boats). Many thought they were also in 10163, but somewhere along the way they vanished. The absence of pontoon boats helped defeat the bill by removing several very emotional supporters of pontoon boat propeller issues. Loosing them, the remaining advocates were not enough to defeat the attack launched on the proposal by the industry. Thus propeller guards and propeller safety devices were suppressed.

- Refused to respond to our challenge to the data they provided. We challenged NMMA (National Marine Manufacturers Association) to respond to six errors we identified in their cost estimate (see pages 83-86 of our houseboat report). NMMA refuses to respond to our challenge and their grossly inflated cost estimate continues to be cited by others as fact. By failing to respond and recognize their errors, the industry is able to perpetuate their false information and stop propeller guards and other propeller safety devices from gaining a foothold on houseboats from which they could be further improved.

- Protocol Does Not Allow Changing Prop Pitch – The Propeller Guard Test Protocol currently being developed by the U.S. Coast Guard tests boat performance with and without the propeller guard. The protocol does not allow changing the propeller to a lower pitch when the guard is mounted. Guards create at least some drag. This drag reduces peak engine RPM and thus peak performance of the boat. Boaters often reduce propeller pitch by one step to allow the engine to rev back up improve performance. The fact that forcing boats to use the same prop (with and without a guard) will amplify any performance degradation of guards has been known for decades (see Reed’s July 1987 Report pgs. 13-14). Refusing to allow the guard to step down in propeller pitch AND/OR reduce propeller diameter will hurt the performance of the boat in the guarded condition in many instances. The performance of the boat with the guard does not do as well in the test as it could, guards will look bad, and the further development of propeller guards will again been limited.

- No efforts were made to verify the ability of a propeller to suck in the “hanging chimes” has any correlation to the propeller pulling in humans or human limbs. Several of the propeller safety devices performed less effectively than on open propeller in some situations. Thus their development has been delayed, perhaps without merit.

- No boat hull at SUNY. No testing was done to verify a propeller’s ability to pull “hanging chimes” inside a propeller guard where they would be struck by the propeller was different with or without a boat hull. By not including a boat hull, the guards and other propeller safety devices were not fairly tested and their results have since been used to delay the development of propeller guards and safety propellers.

- No hull at SUNY but, you must use the same hull in court. The industry has long bashed plaintiffs testing propeller guards on exemplar boats (typically same model and same year) saying that every hull is an individual with its own characteristics and boat hulls are critical to the performance of a guard. They say that if by some means a propeller guard happened to work on a similar boat, it does not mean it would have worked on “the boat.” But at SUNY they did not even use a boat. By claiming both sides (hulls are critically important and hulls are not important), the industry has slowed the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- Protocol Permanently Fixed Ratings by Guard Type. The Propeller Guard Test Protocol currently being developed by the U.S. Coast Guard tested traditional rings, cages, and concentric ring guards in State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo’s circular tank. They used that data to rank the ability of these guards to protect the hanging chimes. Some guards, like the 3PO Navigator, have a rear screen that swings up when underway to reduce drag. Not testing with that screen leaves the 3PO Navigator labeled as a guard that will pull chimes (and seemingly people per the protocol) in from the rear when it will not. This limits their ability to sell the guard and thus its further development.

- 1989 All Over Again. When asked for public comment, we suggested those involved in developing the protocol sign a pledge that they would not sign on as boating industry expert witnesses like Jim Getz and Robert Taylor did after the 1989 NBSAC study was published. I told those currently working on the protocol, that by signing a pledge they would remove the cloud of doubt over their protocol (is it really purposefully being designed to fail propeller guards). They did not respond. By failing to take such a pledge they indicate this project may be maligned just like the earlier one. If it is, the development of propeller guards will again be suppressed by the industry.

- The protocol labels all guards as having blunt trauma issues at 15 mph. We have previously recommended three devices that could reduce blunt trauma issues (two of them long ago patented by Brunswick and one recently patented by Teleflex) that could reduce blunt trauma issues but the industry refuses to test them. Along with them, the Balius guard that swings up on skis would have minimal to no blunt trauma issues because it is up out of the water when underway in forward. By failing to test these technologies they automatically label all guards as blunt trauma at 15 mph and reduce their acceptance. As a result the further development of propeller guards is limited. Reference: see page 135 of our houseboat report.

- The protocol is complex and expensive to conduct. The propeller guard test protocol currently being developed is very complex and will cost thousands of dollars to conduct on a single propeller guard. As a result small manufacturers and inventors will not have the financial resources necessary to have their propeller guards tested and will be tossed to the sideline, limiting their further development. The industry has done nothing to lower this barrier to entry.

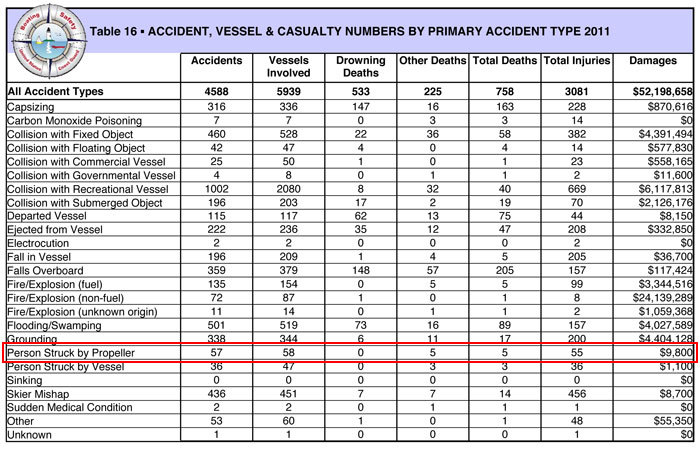

- One industry expert continues to quote Event 1 statistics to represent the total number of propeller accidents, injuries, and fatalities against our best efforts to correct him. Ralph Lambrecht, longtime industry expert witness, continues to quote Event 1 statistics as representing the total number of propeller accidents even after our repeated efforts to correct him. Continuing to publicly spout off low-ball false statistics misleads the public and slows the development of propeller safety devices.

- The boating industry has NEVER joined us in our efforts to correct the use of Event 1 statistics in the media to represent the total number of propeller accidents, injuries, or fatalities. We continuously encounter news media quoting Event 1 statistics as the total number of propeller accidents, injuries, or fatalities. Sometimes even using our page devoted to explaining propeller statistics to reporters, we are still unable to convince them, like in the 2011 Stephen Keller fatality. By continuing to allow Event 1 statistics to perpetuate, the industry downplays the true number of reported propeller accidents, and the development of safety devices is slowed. In addition, we (Propeller Guard Information Center) have to spend a lot of time trying to correct those errors that could be better spent on other propeller safety issues.

- The boating industry has NEVER joined us in our efforts to encourage USCG to print their annual report in a manner that prevents confusion between Event 1 propeller accident statistics and the real total number of USCG reported recreational boat propeller accidents, injuries, and fatalities. By allowing the statistics to continue to be printed in a confusing way, they misrepresent the number of propeller accidents and delay the further development of propeller safety technologies.

- Reporting Event 1 statistics as the total number of accidents amplifies errors when reporting Event 1 fatalities as the total number of fatalities. While we grant the number of propeller fatalities reported in BARD is small (21 to 47 in recent years), when the industry and media misrepresent that already small number by using Event 1 fatalities (1 to 8 in recent years) they downplay the need for a solution and slow the development of propeller safety products.

- See Snyder-Getz letter entry in 1989 NBSAC. Mercury fed the 1989 Propeller Guard Subcommittee Event 1 statistics and told them they represented the total number of injuries and fatalities.

- When the boating industry moves to more specific accident counts (certain types of boats or accidents) their errors in reporting statistics are amplified. See the almost countless accident statistics errors identified in our houseboat report.

- Repeatedly claim that almost all propeller accidents are reported to USCG’s BARD database, and that all fatal propeller accidents have been reported (see pg. 122 of our houseboat report for an example). We have identified almost countless propeller accidents not in BARD or not in BARD as propeller accidents, including numerous fatalities. The industry’s false claims help block proposed regulations and proposed propeller safety investigations, which limits the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- By not pressuring USCG for complete accident statistics (many propeller accidents go unreported), the industry frequently points to the few accidents reported as a reason not to address the problem. When the problem is not addressed, the further development of propeller guards and propeller safety devices is slowed.

- By not calling for research to estimate the number of unreported propeller accidents, injuries, and fatalities. By making no efforts to estimate the actual number of recreational boat propeller accidents, injuries, and fatalities, the boating industry is able to hide from those numbers. The industry clings to the small numbers of accidents reported in BARD (the U.S. Coast Guard’s Boating Accident Report Database). We have proposed several ways in which the total number of propeller accidents, injuries, and fatalities could be statistically estimated. We asked for sponsors to encourage a college student to take on this project. The industry remains silent. By burying the real statistics the industry has slowed the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- Failed to join us in requesting USCG get the states that dropped out of Public BARD to get back in. See USCG 2010 BARD Has Been Castrated. By reducing access to individual accident reports the boating industry perpetuates the misrepresentation of the total number of propeller accidents (we can’t show them the ones they missed, and we can’t find those that were misclassified in BARD).

- By not pressuring USCG for easy to understand statistics, some of the historical databases are very difficult to manipulate and understand. Since the data is not easily available, those accidents are not discussed and the drive for reducing propeller accidents is watered down, thus propeller guard development is slowed.

- Brunswick misled two Federal Courts on propeller accident statistics. In the original Brochtrup v. Mercury Marine trial, and in Brunswick’s request for a rehearing, they quoted lower than actual USCG reported propeller accident statistics. Pete Chisholm, Mercury Marine Product Safety Manager and heir to Dick Snyder’s prop guard expert witness position, testified in April 2010 that some unspecified number of people are injured by boat propellers but firmly denied the number was as large as one hundred. At that time the most recent USCG stats available (2008 stats) showed 181 people struck by propeller. In addition it is widely known that many propeller accidents are not reported or not included in USCG’s Boating Accident Report Database (BARD). By perpetuating low-ball fake statistics the industry downplays the need for propeller safety devices and delays their development.

- Claim specific individual propeller accident scenarios are very rare. The industry recently claimed outboards striking submerged objects and flipping back into the boat where people could be injured by propellers were extremely rare (till we posted a list of them). Then they claimed small Mercury tiller steered outboards had never been involved in striking an ejected boat operator (till we posted a list of them). By claiming these accidents are singular or extremely rare, the industry downplays the need for solutions and their development. Often the industry does this by chaining several variables together (like when they said its rare to get hit by an outboard propeller that flipped into a boat after the outboard struck a dredge pipe (then we posted a list of them too). By falsely claiming these accidents are unique or rare, they downplay the need for solutions which delays the development and deployment of propeller safety devices.

- Says we can’t address the problem because we do not have accurate statistics on boat propeller accidents. The industry often says we don’t have enough statistical information to proceed, but they never encourage efforts to gather more accident reports. By delaying the availability of accurate statistics, they delay the development and deployment of solutions.

- The boating industry has suppressed boating accident reports. For example the Robin Tyler houseboat propeller accident happened at a NBSAC member’s rental operation but was not reported to BARD. She even publicly spoke at a U.S. Coast Guard NBSAC meeting and when later faced with a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the Coast Guard replied they could find no record of her or her accident. By suppressing accident reports, the problem looks smaller and solutions go on the back burner.

- The industry makes no efforts to see if high profile propeller accidents are actually reported to USCG and listed in BARD. We continue to find high profile propeller accidents, including fatalities not in BARD. The industry makes not efforts to ensure the gaps are closed that these accidents slip through. By making no efforts to see that these accidents have been reported, the industry continues let them slip away, resulting in low-ball statistics from USCG which slow the further development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- The industry made no efforts to get the hundreds of fatal SAR accidents recorded in BARD. In the 1990’s investigators noted that hundreds of boating fatalities resulting from all kinds of boating accidents worked by USCG’s Search and Rescue (SAR) had been mistakenly classified as “offshore” (over 3 miles out and therefore not to be listed in BARD), when in fact they had been near shore accidents. BoatU.S. received two USCG grants to audit 1993-1997 SAR data. The Inspector General of the United States used those findings and announced and additional 66 to 103 fatalities per year during that period should have been listed in BARD. Those fatalities have never listed. The industry has never called for them to be listed. If the typical fatality to injury ratio seen in BARD applies offshore, there would also be hundreds of injuries per year near shore offshore that were not reported in BARD. By not calling for these fatalities and injuries to be listed the industry downplayed the need for propeller guards and other propeller safety devices which slower their development.

- The industry has often said “approximately 80 percent of accidents occur when a boat is at operating speeds in excess of 10 miles per hour, i.e. normal operating, or planing speeds”. (see NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee report page 12) However, the data does not reflect that finding or at least certainly not for all types of vessels. As a result, those devices designed to protect slow moving vessels AND/OR any speed vessel from the rear get downplayed and their development is slowed.

- Never makes mention of propeller accidents outside the U.S. even when they involve the same boats, drives, and situations. The industry always wants to make the number of instances small. They do that by arbitrarily subdividing any list of accidents into boat types, drive types, years, geographical areas, etc. The resulting “cells” have zeros or small numbers in them giving the impression the problem is small. As a result, the development of propeller safety devices is slowed. Note – some of the accidents they exclude happen on the far side of the St. Lawrence Seaway.

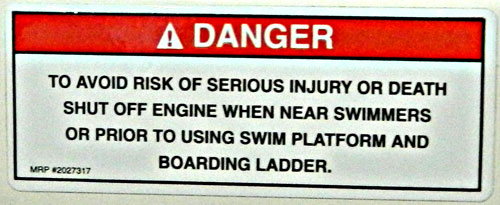

- Does not require longer boarding ladders Refusing to respond to a startling 2010 ABYC video on how shorter boarding ladders contribute to propeller injuries and a recent USCG Call for Public Comment, the boating industry still does not require longer boarding ladders. Industry inaction has slowed the deployment of this easy way to enhance propeller safety. NBSAC’s 2012-2016 Strategic Plan says ABYC (American Boat and Yacht Council) estimates “that adding approximately 10 inches to boarding ladders below the waterline may result in a 75% decrease in propeller injuries during re-boarding.” The industry is still studying the issue almost three years later. We also noticed ABYC took the swim ladder video offline about May 2012. It is no longer visible, but we still have a copy. The industry is even refusing to react to very basic opportunities to make boats safer by just lengthening swim ladders OR by just telling boat companies to investigate longer swim ladders and use them if they work for them. By doing so they have stalled even the most basic propeller safety device (longer ladder).

- Continues to mount boarding ladders right next to open propellers. By refusing to move mounting ladders to the safest reasonable positions, the industry has slowed the development of propeller safety devices (new ladders and swim ladder interlocks designed for safer boarding).

- No aft view from houseboat helm. The industry fails to recognize the importance of houseboat operators having a clear view behind the boat. The industry continues to rely on a “spotter” to be positioned at the stern when they know that does not always happen. Several products and inventions address this problem (remote cameras with displays at the helm, 7 second starting warning beepers, our sound level adjusting backup alarm, our rear doorbell spotter interlock system, Captain’s Mate, and traditional cage propeller guards). The industry continues to place the responsibility totally on the operator which may be operating in the party atmosphere of a rental houseboat. By failing to aid the operator with some of existing propeller safety devices or aiding in the development of concepts still in development, the industry has slowed their further development.

- Fail to recognize the environment on rental houseboats. The houseboat builders and marine drive manufacturers fail to acknowledge the party environment on rental houseboats. They fail to add the training, propeller guards, and other propeller safety devices to make rental houseboats safe. By doing so they slow the development of training programs, training devices, propeller guards, and other propeller safety devices.

- Some boats are designed to unreasonable capacities (too many people can legally be on board to be safe) which can lead to propeller accidents created from poor operator visibility, people falling overboard, or other crowded boat problems. By not adding the necessary propeller guards or propeller safety devices to keep people safe in those situations, the industry has slowed the further development of propeller guards and propeller safety devices. Reference: Bell vs. Mastercraft

- In its quest to add seats, the industry has placed some passengers in peril. By not adding the necessary propeller guards or other propeller safety devices for these hazardous situations, the industry has slowed the further development and deployment of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

Continues to make bow riding of pontoon boats attractive. Pontoon boats continue to be designed so youth or adults can ride on the very front with their feet dangling from the deck while underway. By not changing the design to make this less inviting or creating an interlock to prevent it, pontoons continue to be involved in propeller strikes of bow forward ejections after striking waves or rapidly slowing. Yet the industry continues to discourage the use of propeller guards or other propeller safety devices in these applications. By doing so they are slowing the further development of these products. - The industry seems to have returned to calling propellers a hidden danger. For years, the industry said they were an open and obvious hazard, and as such no guards were needed. Then they said they needed a warning decal (but ABYC says that to have a warning, the hazard must not be obvious – see pages 70-71 of our houseboat report). Plus Mercury Marine recently came out with their Moving Propeller Alert, a series of spinning led lights to alert those in the water that the propeller is spinning). If propellers are in fact a “hidden danger” (which is the title given them by a USCG brochure), they should be protected against. By refusing to apply propeller guards and other propeller safety devices the industry has slowed their further development.

No Response / No Action

The industry often slows the further development of propeller guards and propeller safety devices by doing nothing, taking no action.

- No response to our 2002 call to create a Propeller Safety Consortium to address the problem. As a result, propeller safety is still an issue and development of propeller safety devices has been slowed. The boating industry uses BIRMC (the secretive Boating Industry Risk Management Committee) to scheme ways to limit their risk to propeller suits, but has no similar group to try to solve the problem in the first place. The lack of an industry consortium to pool their efforts on propeller safety issues has significantly delayed the development and deployment of propeller safety devices.

- No response to any of our propeller safety inventions. As a result, the propeller safety inventions we placed in the public domain have not been further developed (at least not in the U.S.).

- No response to request to sponsor college design projects. We posted several senior design project ideas related to boat propeller safety issues on our site. We asked the industry to consider sponsoring some of them, even just by giving the students some free caps, t-shirts, jackets or other branded apparel. After that received no response, we made a more formal plea for propeller safety project sponsors in January 2012. We have since had one response, a diving charter group in another country is interested in sponsoring one of projects. By failing to sponsor these projects, the boating industry has delayed the development of propeller safety devices.

- Refuses to acknowledge the advantages of “flip up” propeller guards. Propeller guards with rear screens that automatically flip up when under way greatly reduce drag and can reduce any boat handling issues. These designs have long been suggested by Don Balius, Guy Taylor, our Flapper, and others. However, the industry has failed to make any attempts of its own in this field. As a result, the development of propeller guards has been slowed.

- Does not use CFD to develop propeller guards. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) holds great promise for designing propeller guards with less drag and minimizing any handling issues. By not using CFD to develop propeller guards, the industry has slowed their further development.

- No efforts to estimate the costs to society and economic costs of propeller accidents. The boating industry has made no efforts to estimate the social and economic impact of propeller accidents. Numerous automotive groups have studied the social and economic costs of automobile accidents, however the boating industry has done no such studies on propeller accidents. By burying these unseen costs, the industry is able to suppress the need for propeller guards and propeller safety devices and limit their further development. The industry has not even examined the social and economic costs of boating accidents in general. Reference: Recent Research on Recreational Boating Accidents and the Contribution of Boating Under the Influence pages 17-19.

- No efforts to followup on long term status of propeller accident victims. The boating industry has made absolutely no efforts to track the long term recovery process of individual propeller accidents victims. It is despicable that we track the long term recovery process of individual large marine mammals and other marine life (whales, dolphins, manatees, even specific damage sites to seagrass) but do nothing to track the recovery of specific people struck by the same propellers. By hiding the grueling life of propeller victims as they go through rehabilitation, countless surgeries, divorces, job loss, long term pain, phantom pain, lack of mobility, being social ostracized for being an amputee and/or severely scared, having to accept care from others, mortgage failures, bankruptcies, all the problems surrounding prosthesis, and countless other challenges, the industry is able to downplay the need for propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- Still does not require all small boats to have kill switches as standard equipment. (see Kill Switches / Lanyard section)

- NMMA refused to respond to our challenge to the data they provided the proposed houseboat propeller accident mitigation regulation. (see Proposed Houseboat Propeller Injury Mitigation Regulation USCG-2001-10163 rejected in 2007).

- Not calling for accurate easy to understand accident statistics as mentioned in several items in the More Propeller Accident Statistics Issues section.

- Dog and pony show The industry uses an experienced, highly trained, well paid legal team and their accompanying expert witnesses to travel around the country squashing propeller injury cases. They have put on their “show” so many times they are sometimes referred to as a “dog and pony show”. The industry’s legal team goes up against propeller accident victims or surviving family members represented by local lawyers with limited resources. The imbalance of power, experience, and money helps swing the judge or jury over to the industry’s view. The industry wins more cases, and the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices is held at bay.

- Uses coordinated defenses. Boat dealers or boat builders are often joined by drive manufacturers including the competition. Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) and Mercury Marine have long worked together in the courtroom on common issues. With billions of dollars behind them (Mercury Marine has Brunswick behind them and OMC still has their insurance company behind them) they can make it rough on local lawyers preparing a case, or in the courtroom. By doing so, they have delayed the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices. This not a crime. They should defend themselves to the best of their abilities in court. It just makes it more challenging for propeller safety devices to see the light of day.

- OMC and Mercury worked together in propeller cases but not to find solutions. OMC and Mercury Marine worked together in many propeller injury cases to defeat plaintiffs. However, they failed to work together in any attempts to develop or improve solutions (propeller guards and other propeller safety devices). Their only joint testing was the litigation testing done on the Snyder guard at SUNY. By failing to work together to create new solutions or improve existing ones, OMC and Mercury slowed the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices.

- Federal Preemption Defense – In the early 1990’s the industry began developing the Federal Preemption Defense (Federal Boat Safety Act of 1971 did not require the use of propeller guards on all boats so states could not require their use on any guards because Federal Laws preempt state laws per the industry’s legal theory). This defense was perfected by the mid 1990’s and was used successfully until December 2002 when they lost in the U.S. Supreme Court (Sprietsma v. Mercury Marine). While the preemption defense was working they just walked into court, said they wanted summary judgement based on federal preemption, and the case was dismissed. This defense significantly limited the further development of propeller guards for several years.

- Struck by anything but the propeller. In legal cases the industry argues the injuries (or the most serious injuries) were caused by striking the boat, striking the leading edge of the drive, striking the torpedo, striking the skeg, or striking anything other than the propeller. The industry tries to take as many damages as possible off the table in propeller injury cases by saying they were not caused by the propeller. This defense plays down the need for propeller safety devices and slows their development.

- Propeller cuts are nice and clean. The industry argues that open propellers make nice clean, quick to heal cuts, while propeller guards would result in gruesome blunt trauma injuries. Many medical professionals disagree. Propeller wounds are frequently infected with all kinds of bacteria and other substances in the water. Fighting infection is a major part of the early stages of recovering from a propeller accident. Afterwards, amputees often fight it for the rest of their lives. By falsely arguing that propeller wounds heal quickly, the industry has slowed the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety solutions. Plus recent studies have shown propeller strikes are more blunt and crushing than previously thought. Reference: Patterns of Trauma Introduced by Motorboat and Ferry Propellers as Illustrated by Three Known Cases From Rhode Island. Journal of Forensic Sciences. Not Yet Published.

- BIRMC. The Boating Industry Risk Management Committee, a subgroup of NMMA (National Marine Manufacturers Association) secretly meets behind closed doors to scheme ways to limit their exposure to product liability suits. Attendance is by invitation only, agendas are not public, and electronic devices have been collected at the door (to prevent recording the proceedings). Conspiring against propeller safety devices behind closed doors is obviously not good for the further development of propeller safety devices.

- Air victims dirty laundry in court. The boating industry will do everything possible to discredit accident propeller accident victims and their families in court. One popular way is to air out all their family secrets in open court (alcoholism, sexual preferences, arrest and jail records, illegitimate children, drug use, incest, adoptions, sexual improprieties, infidelities, bankruptcies, business failures, etc.) And if the victim’s family has no secrets (which is rare), they may make some up. By belittling victims in the eyes of the jury: (1) the industry tries to minimize any possible awards and (2) it discourages others from filing cases. Both of which slow the development of propeller guards and other propeller safety products.

- Air expert witnesses dirty laundry in court. Just like propeller victim’s families have dirty laundry, so do expert witnesses. The industry will air similar personal dirty laundry on experts in court. This prevents some potential experts from entering the fray, and thus limits the ability of propeller guards and other propeller safety devices to have their products best represented in court. (Reference: insinuations an expert witness had a problem with alcohol, we will not justify the industry’s claims with a name).

- Refer to obvious propeller strike victims as alleged prop strikes. In the Decker trial, industry lawyers referred to a well known female propeller victim that showed up at the trial as a “one-armed woman in and out of the courtroom, hanging around the front” and as “another alleged prop strike”. Talking about someone who has been through what that lady has been through, and lost her husband to a propeller as well, as an “another alleged prop strike” is demeaning to all propeller victims. Reference: Decker v. OMC transcript pages 749-755 and Naples Daily News Court Blog Day 9. June 9, 2009.

- Tries to use Admiralty Law to limit legal exposure. Admiralty Law (also called Maritime Law) was established long ago to protect ship owners from large lawsuits if a ship crashed into something valuable and caused a lot of damage. Under Admiralty, a shipowners exposure was limited to the value of their vessel and its contents. This prevented vessel owners from being sued for countless millions of dollars when vessels crash into more valuable ships or structures (like the Oklahoma I-40 bridge hit by a barge, or the New Orleans Riverwalk struck by the Bright Field). In today’s law, Admiralty Law applies to accidents on navigable waters, including those involving recreational boats. Navigational waters are defined as all waters (lakes, waterways, rivers, harbors, oceans, etc.) used by commercial vessels or capable of being used in interstate or foreign commerce (note the actual definition is much more precise). When a recreational boating accident happens in the ocean, in the Great Lakes, in a lake spanning more than one state, or any body of water tied to a river system, the industry often tries to have the case tried under Admiralty Law to limit their exposure. By so doing, it delays the development and deployment of propeller guards and propeller safety solutions because the industry is able to “get off” for the value of one boat. No need for them to buy and install guards if failure to install them only costs the industry a used boat now and then. Note, some states do not allow recreational boats to file to limit their liability under “Rule F” to the value of the boat in Admiralty cases.

- Tries to use Tribal Jurisdictions to escape their responsibility to protect boaters. Several large western lakes are on tribal lands. When accidents occur on those lands the industry tries to claim state and federal laws do not apply. Most tribes do not have typical product liability laws and no real method for the victim or their surviving family to recover. By trying to shift to a jurisdiction in which the industry has no duty to propeller accident victims the industry limits their need for propeller safety devices. The industry has no reason to use propeller safety devices when they have no duty to protect people. This and other similar legal tactics have slowed the development of propeller safety devices. Reference: the Listman case arising from a 2003 propeller accident on Pyramid Lake on a Nevada Paiute Tribe Reservation.

- Argued against letting statistics in, then argued no statistics were provided. In Jacob Brochtrup v. Mercury Marine and Sea Ray, the industry was able to exclude three plaintiff expert witnesses who were going to testify about the frequency of propeller accidents (Kopytko, Mendez-Fernandez, and Price). The industry said their testimony would be of limited value in reaching a decision in the case that and any value their testimonies might contribute would be substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice. Then during closing arguments of the second trial Mercury argued that Brochtrup presented no evidence the product was unreasonably dangerous because they presented no evidence that these accidents “happened a lot.” The District Court Judge later made the following statement outside of the presence of the jury:

“But more prejudicial in your argument, and almost caused me to come out of my seat, is I sustained your motion in limine to keep off the stand Phyllis Kopytako. I sustained your motion in limine to keep of the stand Miguel Mendez-Fernandez. I sustained your motion in limine to keep off the stand Charles D. Price because you said that the prejudice of all these other propeller injuries outweighed the relevance, and then, you’ve got the gall to sit up here in closing arguments and ask the jury why didn’t they present evidence of that. The Court finds that very prejudicial and very wrong.”

By keeping the frequency of accidents out the first and second trial and then telling the jury that Brochtrup presented no evidence of the frequency of these accidents, Mercury was able to hang the juries and delay the further development of propeller guards and propeller safety devices. Reference: U.S. Court of Appeals 5th Circuit Brochtrup v. Mercury Marine and Sea Ray 10-50534, Response Brief of Appellee filed 29 December 2010. Note – Brochtrup later won a $3.8 million award.

- Big Investment in Defense In Decker vs. Boston Whaler and OMC, Plaintiff lawyers were able to get Robert Taylor to admit his firm, Failure Analysis Associates, had been paid an estimated $60 million to defend manufacturers in propeller guard cases per Naples Daily News. While the actual transcripts bring that estimate into question, there is no doubt the industry has spent tens of millions of dollars defending itself in propeller cases. With that much money going to fight proposed propeller safety devices, it will be very hard to turn them around and encourage them to invest some of that money in solutions. Their high cost defense is not only suppressing the development of propeller safety devices by others, it is suppressing internal development as well. For example, the only thing the industry has to point to from the last couple decades is Mercury’s Moving Propeller Alert (some LEDs flashing in a rotating pattern).

- The future is now. In Elliot v. Brunswick, U.S. Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit, decided June 25, 1990 some estimates were made of when a truly optimal guard might be available from the industry itself:

“At trial, moreover, the experts called by both parties agreed that no feasible guard existed that could be adapted readily to existing motors. For example, one of plaintiff’s witnesses, Dr. Arthur Reed, a naval architect, estimated that Mercury might develop an appropriate guard after a total of ten or eleven years of effort by biomechanical engineers, hydrodynamic engineers, structural engineers, and materials engineers, followed by an additional four years of prototype testing. Dr. Reed frankly conceded, in short, that, in his view, “all of these guards need technical development before they are ready to really be marketed.””

1990 plus 11 years plus 4 years = 2005. Its now 2012, what happened?

- Yamaha pulled its propeller guards from public view. In the Spring of 2012, Yamaha UK announced a new stainless steel propeller guard for its flood rescue outboards (small two stroke outboards used in rescue boats). In October 2012, we wrote three posts on their new guards including Yamaha’s claim they were essential to reduce risk with people in the water. On 8 Nov, 2012, the eve of the NBSAC90 Meeting in Watsonville, California, we noticed every single reference to the new propeller guards Yamaha UK Pro had been bragging about for months had been scrubbed from their site. No more UK Pro Outboard Accessory brochure, no more news coverage of the Lincolnshire Fire and Rescue Boats, no more mention of all the good things the guards were doing, no more mention of how they were essential to reduce risk to people in the water, and not more mention of how they have guards to fit every outboard. Its as if they never existed.

We tried to contact one of the Yamaha UK marketing executives involved with the flood rescue outboard package but they will not return our email. We posted an open request to Yamaha asking why they pulled the guard literature and have had no response. The complete blotting out of the existence of the guard and no response, now leads us to believe this may have been a legal move to hide their positive statements about propeller guards in general. By coming back in line with the rest of the industry’s rhetoric, they preserve the line of defense against propeller guards and limit their further development. The decision to remove these materials from public view may have been broader than just Yamaha. Others may have complained to Yamaha’s about their statements in favor of propeller guards and encouraged them to remove them from public view. (like the industry worked together to ban the Don’t Wreck Your Summer PSA.)

- Laughing of test crew at SUNY 1990. The 1990 joint tank testing at SUNY (State University of New York at Buffalo) was filmed. The test crew can be heard laughing and joking as the propeller guard impacts a dummy’s head. Interestingly, Robert Kress (directing the efforts) comes in and starts yelling and cursing at them because their voices are being taped (as is his). By secretly joking about propeller accidents the industry reveals their real intent to delay the development of propeller safety devices.

- Design Research Engineering’s Crew Squeals at Listman Test. In Robin Listman vs. OMC, Kelly Kennett (independent consultant) provides expert witness testimony for the defense, along with Robert Taylor from Design Research Engineering. Part of Mr. Kennett’s testimony relied on feeding simulated human arms into an immersed spinning boat propeller with a guard on it. The crew from Design Research Engineering conducted and filmed those tests. At one point, an arm enters the guard, becomes caught in the propeller. The crew squeals and celebrates ecstatically. That clip was played in court as the plaintiff’s lawyer questioned Kelly Kennett about any possible bias in his testing. Those preparing evidence for this industry expert were obviously biased which can effect the outcome of trial which effects the future development of propeller safety devices.

- Response to OMC Australia when started selling OMC’s guard to surf life saving groups. Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) has long made a small ring type guard they claim is solely for protecting the propeller. When OMC Australia teamed it with a rear “mask” and started selling it like hotcakes to the Australian surf lifesaving market, OMC called them on the carpet and told them guards do not work. But, a few years later, OMC Australia slipped a clip about how great the guards were still working and saving lives into OMC’s corporate newsletter. See the OMC Australia entry in our list of Boat Builders Offering Guards.

- Mercury Marine developed, patented, and sold propeller guards to the U.S.Marine Corps. Mercury tries to play this application down and says they were only used of boats that were at rest or nearly at rest to protect Marine’s feet as they were loading and unloading the boats. The original government documents said the guard was to “give Marines operating the Rigid Raiding Craft (RRC) or working in the water (surf zone), protection from propellar (sic) blades.” Yes, Mercury had them later change that language, but it was obvious what the Marines wanted. Marine Corps. Mercury and OMC together later tested this guard, we call it the Snyder Guard, at SUNY in 1990. They found the guard not to be safe (see 1990 SUNY testing section). By failing to showcase this successful application, the boating industry set back any future development of propeller guards. While Mercury supposedly proved the Snyder guard was no good at SUNY in 1990 and continued to repeat those findings in public and in the courts, they paid a $930 patent maintenance fee to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office four years later in 1994 to keep their patent in force until September 1998. Continuing to maintain the patent indicates they thought it had promise, but were telling us otherwise.

- OMC – Project 441 and Project 443). Outboard Marine Corporation ran two internal propeller guard development projects resulting in propeller guard patents, but OMC similarly discredited them in their own testing. By discrediting their own guards, OMC slowed the future development of propeller guards. The parallel developments at OMC and Mercury may have been an effort to develop a guard in case the other guy launches one.

- Disney World fiasco. Mercury Marine had a lot of small outboard motors on rental boats at Disney World with propeller guards on them. About 1989, Brunswick started being challenged in the press and in propeller injury court cases, if guards were no good, why did Brunswick put them on Disney World’s boats? Brunswick removed the guards. They said Disney wanted them pulled because they were not safe. The only problem was that Disney was lauding accolades on how great the guards were working and how safe the boats were to the press. As a result of pulling the guards from Disney’s boats the further development of propeller guards was slowed.

- Never surveyed its customers. Major industry players have never surveyed their customers to ask them if they have any interest in propeller guards. By never surveying their customers they delayed any demand for propeller guards and slowed their development. Reference: Snyder deposition in Pree vs. Brunswick Sept. 20, 1991. Pg. 65 and Kueny deposition in Listman vs. Porsow October 6. 2006. Approximately page 48.

- Never advocate for safety devices. Dick Snyder, Mercury Marine’s internal propeller accident expert witness, was asked in Tyler v. Verschuer, et al., “Can you tell me of any safety devices or technology that you’ve openly advocated for implementation in boating?” All he could come up with was a ladder that somehow requires some new articulation technology so people stay further away from the propeller while boarding. But he is not sure how that can be done. By failing to support any existing safety devices or technologies the industry slows the development of all boating safety devices. Reference: Snyder deposition August 17, 2006 pgs. 268-270.