Mercury Marine / Dick Snyder 1989 Propeller Guard

Dick Snyder, Mercury Marine’s expert witness in propeller guard cases, designed a propeller guard back in 1989.

Placing the event in historical perspective, this was a very eventful time. The U.S. Coast Guard NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee was formed on May 11, 1988, met twice more in 1988, met in May of 1989, then delivered their final report in November of 1989. Also in 1989, the Institute for Injury Reduction, led by Ben Kelley, was loudly calling for the use of propeller guards. In November and December of 1990, Mercury Marine and Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) ran the propeller guard tests in the circular tank at State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo using the Snyder guard on a OMC outboard. In 1991, Mercury Marine was able to convince a court to dismiss a propeller case based on Federal Pre-emption (a defense the boating industry then employed for almost a decade).

It seems like an odd time for Mercury to be developing a propeller guard. Documents indicate they were probably attracted by the potential to sell a large number of outboards to the military. At that time Rigid Raiding Craft (RRC) were 18 foot Boston Whalers powered by twin OMC 70 horsepower outboards. Note, this was before Brunswick owned Boston Whaler.

The military was in process of beefing up its riverine, littoral, brown water capabilities. Rigid Raiding Craft (inflatable hard bottomed boats) were announced in 1987. Rigid Raiding Craft were to be directly launched from internal bays of larger vessels offshore, to carry soldiers to shore for quick actions, then return them to the larger “Mother Ship”. They were often used for Over-The-Horizon (OTH) raids.

Or, maybe Mercury Marine became involved because they heard over a dozen propeller guards were going to be participating and they wanted a front row seat to view what was going on.

Or, maybe Mercury Marine was just being patriotic and wanted to help out our men in uniform.

Truth is, we don’t know why, we just know they did.

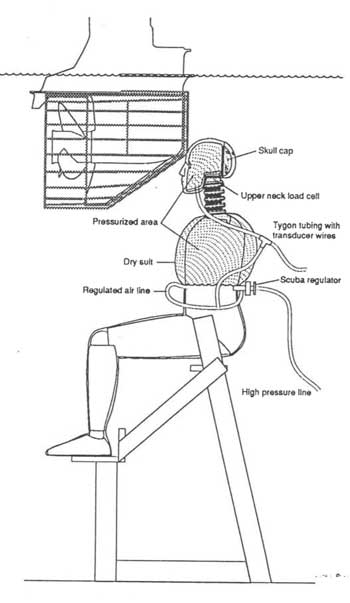

Mercury’s Snyder guard was basically a wire cage type guard, open to the rear. Mercury noted they could adjust the wire spacing to limit a ball of a given size from passing (similar to the Surf Guard design test).Mercury repeatedly stated the guard was to reduce the risk to Marines that were boarding and debarking from the boat in shallow water while the engine was still running. Mercury also noted the guard itself could cause severe or fatal injuries if made struck a person at or above 8 miles per hour. The guard was not recommended for continuous use above 30 mph and Marines were to be instructed not to reach out in any way it they lost their footing or they might push a hand or foot into the open rear area of the guard and suffer injury and or entrapment. Mercury Marine also included the disclaimer, “This device is not intended to and will not prevent very serious or fatal injury when used in other foreseeable applications, and cared should be taken to see that this device is not placed in general use.”

Among the various documents available from that era are :

- April 14, 1989 Mercury Marine lab report on on water testing various wire thicknesses of the Snyder guard.

- May 30, 1989 letter to NBSAC Propeller Guard Subcommittee Chairman from Richard Snyder of Mercury Marine summarizing his work with the U.S. Marine Corps, delivered at May 1989 Subcommittee meeting.

- Undated two pages of specifications and descriptions of the guard by Mercury Marine labeled RRC.

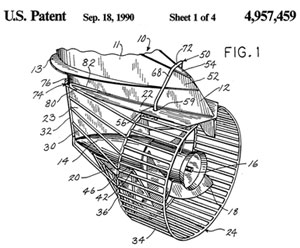

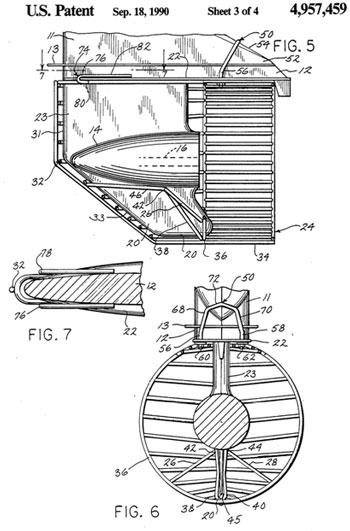

- August 23, 1989 Mercury Marine filed the patent application for Dick Snyder’s propeller guard (called a propeller shroud by Mercury).

- September 19, 1989 Mercury Marine requisition document approving the purchase of four of the guards from the external manufacturer (Wald Wire).

- November 8, 1989 Marine Corps Research Development and Acquisition Command order for non-personal services for on water testing the propeller guards on RRC from November 27, 1989 through 1 December 1989 at Coronado California, and for a written test report from Mercury Marine. The quote was basically for instrumenting the boat with two tachometers, a speedometer, and capturing data on the Mercury’s Product Data Logger (PDL).

- November 13, 1989 Marine Corps Research Development and Acquisition Command Modification of Contract to Mercury Marine. Added that the test rod will be a mannequin leg with a combat boot on it and a note that “The guards will be unacceptable if there is any slippage, drag, or resistance during maneuvering.”

- December 13, 1989 Mercury Marine memo noting there were originally expected to be 13 solicitors sending propeller guards to San Diego for testing by the military at the Amphibious Base, Coronado, San Diego, California. However, none had arrived by November 22, 1989. Mercury’s wire guards were maneuverability tested there on November 28, 2011. Both of Mercury’s guards broke during that testing.

- September 18, 1990 U.S. Patent 4,957,459 for Propeller Shroud With Load Bearing Structure issued to Mercury Marine. Dick Snyder was the inventor. The patent solely focuses on the mounting method and its ability handle impacts. The patent says nothing about any protection the guard might provide or even what purpose it might serve.

- February 24, 1994 Mercury Marine / Brunswick Corporation paid the first maintenance fee on the patent to keep the Snyder patent alive, long after the SUNY testing.

- September 20, 1998 the Snyder patent expired because Mercury Marine / Brunswick Corporation failed to pay the second maintenance fee.

The history of the Mercury Marine / Snyder guard is also discussed in Richard Snyder’s April 25, 2006 testimony in the Ard v. Brunswick propeller case on pages 58 to 68. Mr. Snyder reports he started removing some of his wires to reduce drag as the competition focused on the Snyder guard and Chadwell’s PVC ring guard. Mr. Snyder reports the Chadwell guard allowed the boats to go a little faster, but was failing gearcases at the skeg and anti-ventilation plate where it was attached, so the Marine’s were leaning toward the Mercury guard. But, the Gulf War broke out and the Corps wanted the guards immediately. Mercury finished them later and shipped them, but has no idea whatever happened to them. (Other records indicate Mercury shipped about 13 units). The Marines eventually ended up going with twin 70 horsepower OMC pump jets.

The history of the Snyder guard is also recounted in Mr. Snyder’s testimony in James Pree v. Brunswick Corporation. September 20, 1991. Pgs. 67 to 75.

A common topic in propeller guard trials is if propeller guards don’t work, why did Mercury Marine / Brunswick patent this one and sell it to the U.S. Marine Corps? Mercury and the Boating industry claims the Snyder guard was designed to protect soldiers boarding or debarking from the Rigid Raiding Craft in shallow water when outboard motor was running and the propeller was still turning, with the boat stopped or nearly stopped. Mercury says the Snyder guard was not designed for normal use.If the Snyder guard was really designed to keep soldier’s feet (combat boots) out of the propeller when the boat was at rest, why is the mesh so tight? Mercury knew more wires meant more drag when the boat was underway.

If we believe Mercury is telling the truth, we are left to wonder why the Snyder guard was selected from all other guards to be the guard tested at SUNY (State University of New York) in the large round tank in 1990. Mercury Marine and Outboard Marine Corporation (OMC) conducted extensive in water tests there in November and December 1990 using the Snyder guard on an OMC outboard.

If we are to believe the Snyder guard was purely designed to keep feet (combat boots) out of the propeller in shallow water when the boat was at rest, and Mercury Marine’s accompanying disclaimer, “This device is not intended to and will not prevent very serious or fatal injury when used in other foreseeable applications, and cared should be taken to see that this device is not placed in general use.”, why would they have even considered it as the guard to test at SUNY?

Perhaps they selected it because the wire cage closely clings to the drive resulting in a sharp vertical leading edge that comes to a point where the leading edge of the drive bends back at the skeg (just below the torpedo). At SUNY, Mercury and OMC lined that sharp point up and repeatedly struck underwater dummies in the forehead / skull with it. They also used the sharp leading edge of the guard to strike cadaver arms and legs. The predictable results were used to say all guards were unsafe.Or perhaps they selected it to make sure no one could use it against them. They did not want Plaintiffs to be able to say Mercury sold a guard, why didn’t Mercury use guards. So Mercury tested it at SUNY to refute that claim.

The bottom line is we don’t know why they picked it, just like we don’t know why they responded to the Marine Corps solicitation for guards for the Rigid Raiding Craft. We just know they did.

As long as we are discussing unknowns, anybody ever wonder why Mercury and OMC:

- Did not select one of the many guards that attach behind the leading edge of the drive instead of the Snyder guard to test at SUNY.

- Did not select a guard designed for use in normal operations with a rounded front to test at SUNY.

- Did not select the guard Balius patented way back in 1975 that automatically swings up out of the water when under way (U.S. Patent 3,889,624) to test at SUNY. There would not have been anything in the water to strike the dummy except the drive and propeller. (Guard designed for use with boat at rest or in reverse).

- Did not try striking the same dummy in the forehead with the leading edge of the skeg (lower part of the drive) at SUNY.

- Expressly forbade any testing without the Snyder guard being in place at SUNY (no testing to be done with an open propeller).

We also find it interesting, that as of July 11, 2012, the Richard Snyder patent which Mercury Marine says was designed for this one special application (protecting the feet of soldiers wearing combat boots while boarding and debarking with the boat stopped in shallow water) and NOT for general use has been cited 25 times as a reference by other U.S. patents (mostly propeller guard patents). If it has no application to general propeller guard use, why do so many other patents cite it? Are some of those cites made by patent examiners?