FLIR receives Virtual Propeller Guard Patent

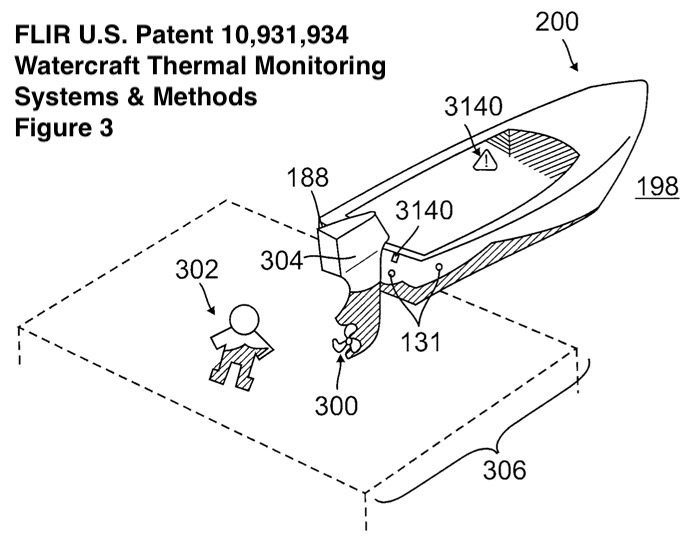

This patent teaches the use of one or more imaging modules on the vessel scanning one of more areas around the vessel using thermal or non thermal imaging to detect people, debris, or docks in the water near the vessel. Once the object is detected, the operator can be alerted to its presence including its heading, distance, what it is, and could even be shown an image of it.

The control system can take that input (sees person, debris, or dock near the vessel) and automatically steer the vessel, accelerate or decelerate, or stop the propeller depending upon the object and situation.

FLIR describes the system as having an imaging component and a control component. The imaging component is referred to as monitoring modules. They specifically note one or more monitoring modules may be placed at the stern (one place to monitor people near the propeller). Each module may include thermal imaging, non-thermal imaging methods or both thermal and non-thermal imaging capability.

The system may include perimeter detection, meaning it can recognize when someone goes overboard similar to systems on some cruise ships.

The system can take control of the vessel when swimmers or a man overboard situation has been detected, as well as assist in various modes of operation such as docking or tactical debris avoidance.

We, PropellerSafety, note tactical debris avoidance may have application to bass boats striking floating logs and debris, their outboard motors breaking off, and flipping into the boat while still under power. FLIR’s patent may one day be applied to that field as well as being a virtual propeller guard and automatic docking system.

Monitoring modules may be embedded in the hull or other portion of the vessel, be in an add on structure such as a pod, they may be mounted flush with the hull, protrude from the hull, or be recessed in the hull behind a visually opaque, infrared transparent housing (not visible on the hull to the casual observer).

Image capturing capabilities may include stereographic images (3D).

Imaging capabilities may extend below the water by use of visible camera, sonar, radar, infrared technologies.

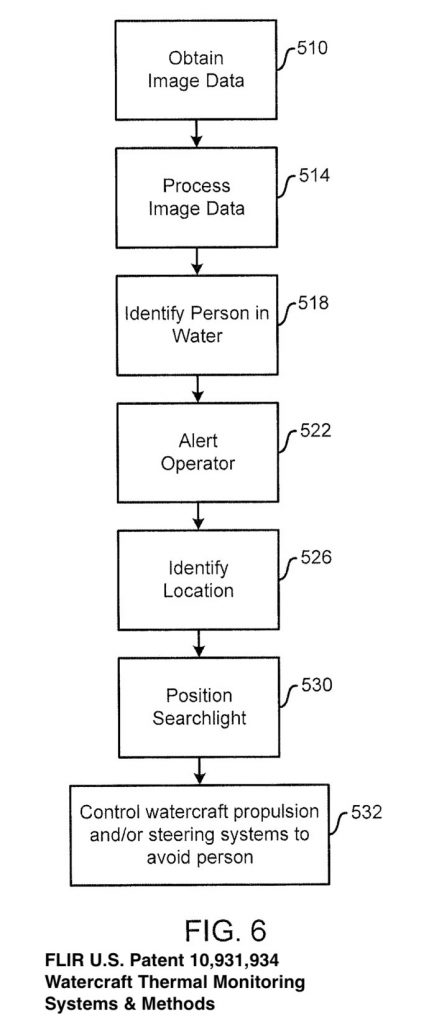

When a person or near collision object is identified, a search light could be automatically focused on the person or object.

Multiple modules may have overlapping coverage to secure full coverage around the boat.

FLIR notes video analytics can be applied to a series of thermal images to produce TIDAR (thermal infrared detection and ranging, or thermal image detection and ranging. They can use the parallax shift between two image capture components which can be much wider than the distance between human eyeballs to range the object. FLIR says this can provide a hyperscopic view with enhanced depth accuracy.

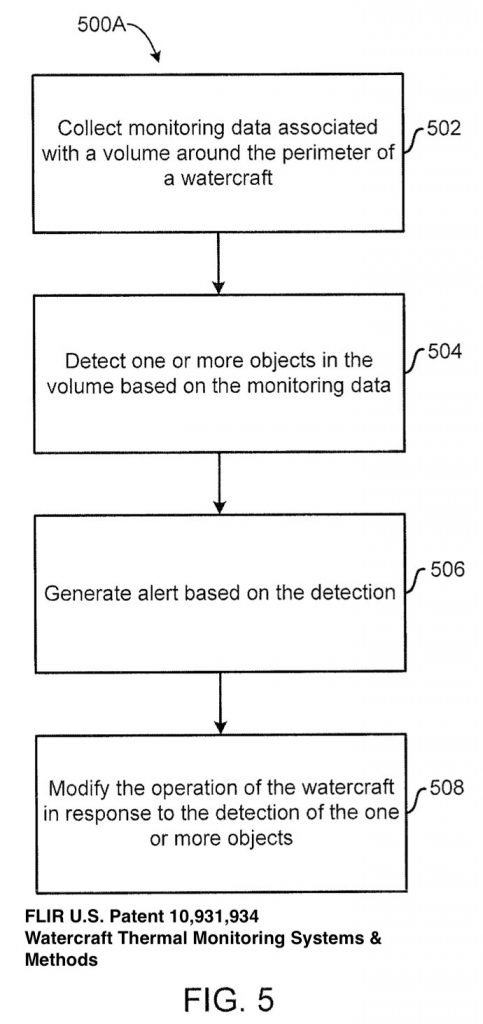

Logic of the System

System logic is explained in FlIR’s patent image below.

Alerts may be directed to the operator, the swimmer, and/or passengers depending on the situation. Alerts may include an audio or visual signal such as a siren, flashing light, or buzzer.

Many additional technologies may be interfaced with the system including trip wires, laser array systems, fused thermal and nonthermal images, as well as combinations of the other technologies as well.

When swimmers or other objects are detected, alerts may include identification of the object, range/distance, bearing, and an image.

Various methods are used to discriminate various objects. Thermal imaging is useful in discriminating humans from water based on their body temperature.

Threshold discrimination may be performed to distinguish between living and nonliving objects. Shape, size, structure, aspect ratio, velocity, and other measures may also be used in discriminating objects and determining when to send an alarm. For example a falling deck chair or cup of coffee thrown overboard may be purposefully ignored.

The system may zoom in on people to supply improved images for recognition.

Radar or sonar may assist in determining position, range, and heading to a person in the water.

The event such as man overboard or person in the water may be recorded along with the location and time to assist in Search and Recovery (SAR) operations. Location and time information may be recorded directly on the images.

Operation of the watercraft may be modified based on detecting a person in the water. For example the boat might be steered away to avoid striking the person or power to the propulsion system might be cut to avoid striking the person with the propeller.

The actual process of detecting, identifying, and alerting in the event of a swimmer being detected is shown in Figure 6 of the patent, copied below.

Suspect Person in the Water

Sometimes the system is positive it detected someone in the water. Other times it suspects someone is in the water (see Patent column 10 lines 13-15).

The patent talks about discriminating between various objects but provides minimum details on how to handle a “probable” swimmer or person overboard detection.

Other patents have spoken of fusing different data sources and trying to generate a numeric probability or range of probabilities, then set some acceptable level at which the alarm would be raised in order to prevent frequent false alarms.

Some Comments About the Patent & It’s Path Through the USPTO

This patent is extremely thorough in its Detailed Description. The patent is 34 pages in length, includes detailed drawings and other tools to make certain they disclosed their invention as broadly as possible.

This patent was issued 2 March 2021. We noticed it was filed way back on 15 december 2015, over 5 years ago.

The patent eventually issued with 21 claims including two independent claims, one for the system (hardware) and one for the method.

Taking a long time to go through the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) system usually indicates they had trouble convincing the patent examiner their device was unique, and especially that some specific claims highly valued by the assignee (individual or entity to whom the patent rights are assigned) were unique.

We looked at the Public PAIR (documents recording the patent’s path through the system including evidence, information, documents, references, and letters from USPTO and the assignee).

Per Public PAIR, FLIR encountered multiple non-final rejections and multiple final rejections. They kept powering forward so FLIR must have placed considerable value on getting this patent issued, Early on they faced issues with the Haley patent, U.S. Patent 8,581,982. As FLIR tried to skirt those issues they started running into other patents. That is why this patent took so long to issue.

Very basically a patent’s claims describe the size and scope of one or more virtual clouds of the universe the claims cover. Assignees want those clouds to be enormous. Patent examiners want the clouds to be small. Prosecuting a patent though the system involves give and take between both sides to determine the location, size, and scope of the resulting cloud(s) if any are allowed.

One specific point FLIR was not able to overcome was the examiner requiring them to limit their claims to stereoscopic images. One independent claim is limited to stereoscopic infrared images and the other one is limited to stereoscopic infrared and stereoscopic visible light images. While the discussion of their patent teaches of much broader applications of their approach, the actual claims are limited to stereoscopic images.

It would have taken a considerable bankroll to fund all the updates, fees, and man hours associated with prosecuting this patent through the system.

We, PropellerSafety, are glad they did. We wish FLIR continued success in this field and look forward to seeing the fruits of their efforts in the marketplace.