Mercury patents log strike monitoring system

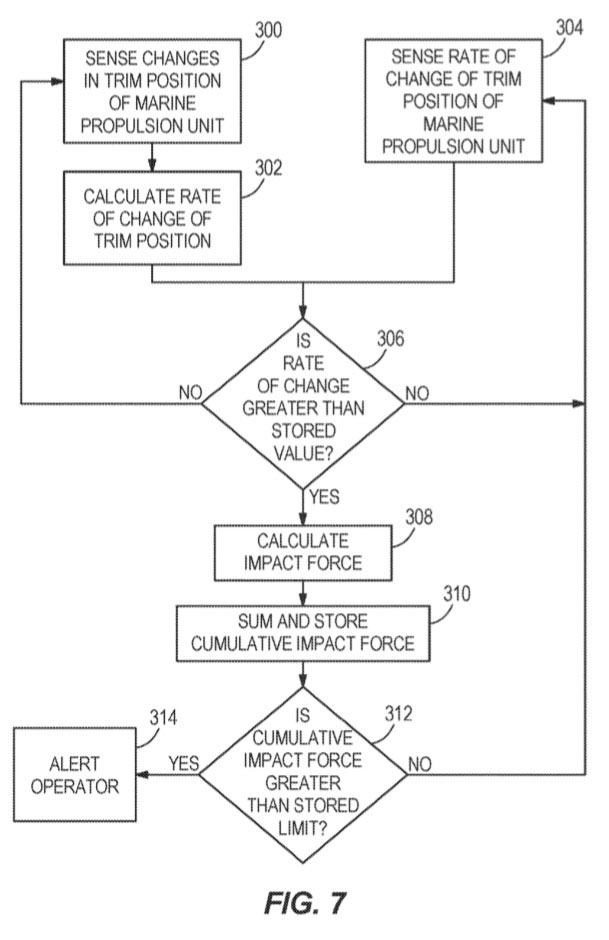

Brunswick / Mercury Marine was issued U.S. Patent 10,214,271 Systems and Methods for Monitoring Underwater Impacts to Marine Propulsion Devices on 26 February 2019. Steven J. Gonring and Mark D. Curtis are listed as the inventors.

The patent teaches detecting rate of trim (rate of tilt) to determine an impact occurred. If the drive is tilting more rapidly than normal, it may have struck something. Brunswick talks about alerting the operator, turning the drive off during severe impacts, estimating the force of impact from changes in the rate of trim, storing the resulting data, and evaluating the remaining useful life of the drive or signaling the outboard should be serviced. This system is designed to report impacts above a given level. It does not address impacts that break the outboard off the boat, except to suggest that several impacts above a given level could make an outboard more likely to fail in future impacts.

Near the bottom of this post we identify a Suzuki patent in Japan that may create some prior art issues for Brunswick’s / Mercury Marine’s recent patent.

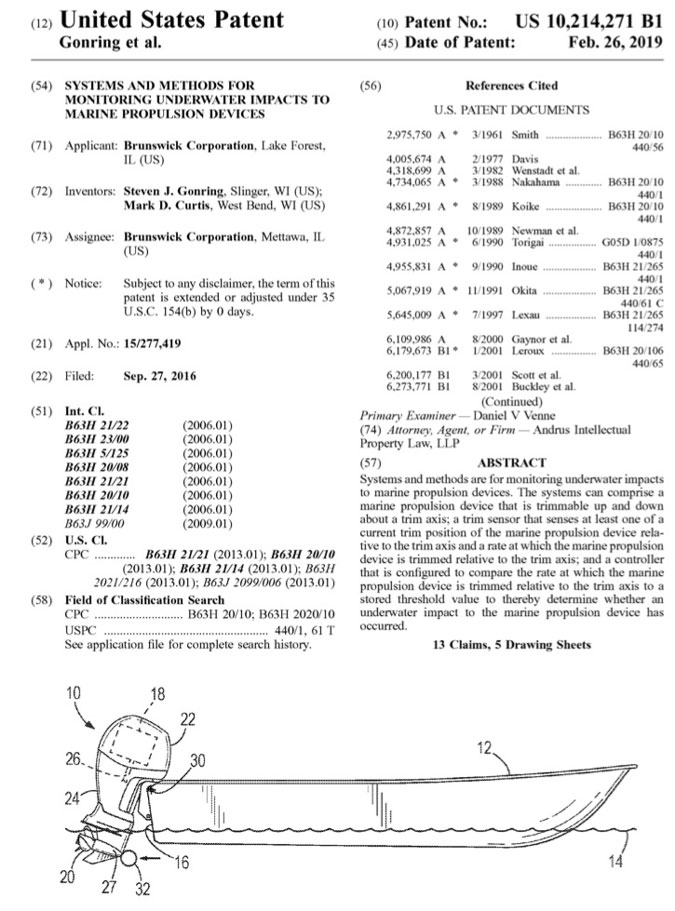

The patent opens by describing log strikes as a “trail over event” as seen in the image below:

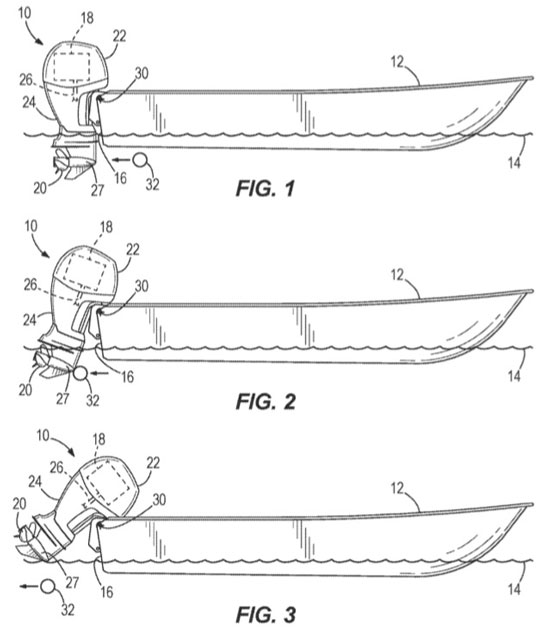

Then the patent explains how they will focus on rate of change of trim to detect impacts:

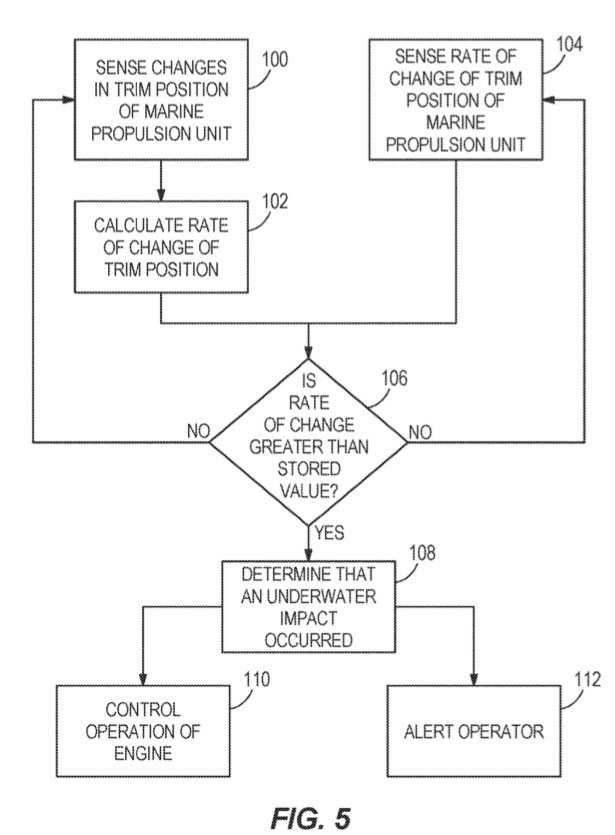

Then shows how they plan to calculate impact force based on rate of trim (tilt) during the strike:

Patent Details

Brunswick does a nice job of listing several patents, mostly Brunswick patents, leading up to this one.

The patent notes that multiple high speed impacts can reduce the lifespan of marine drive components.

Beginning in column 3 line 64:

“The present inventors have also found that high-speed impacts with underwater obstructions can potentially cause serious damage to the marine vessel and possibly endanger passengers onboard the marine vessel. The inventors have therefore found it to be desirable to provide improved systems and methods for controlling operations of the marine propulsion device (for example shutting the device off) when a high-speed impact occurs–so as to prevent further damage to the marine vessel and to protect the occupants of the marine vessel from harm.”

Beginning in column 4 line 15:

“For example gearcase housings and/or driveshaft housings on marine propulsion devices are often constructed of relatively lightweight aluminum, which can have limited impact strength. If the aluminum is in use over a long enough period of time, under a given load, it will ultimately require repair or replacement. As such, the present inventors have found it to be desirable to provide systems and methods that determine and/or predict such future maintenance and/or replacement requirements of these aluminum components based on cumulative effects of current and historical impacts from underwater obstructions.”

Beginning in column 5 line 45:

“Thus, as shown by comparison of FIGS. 1-3, a high-speed impact engagement of the marine propulsion device 10 with the underwater obstruction 32 can cause a forced/involuntary, rapid trimming action of the marine propulsion device 10 from the trimmed down position shown in FIG. 1 to the trimmed up position shown in FIG. 3. In certain instances, such impact engagement can damage the marine propulsion device 10 to an extent which the marine propulsion device 10 requires immediate repair or replacement. Repeated impact engagements can also wear down certain components of the marine propulsion device 10, such as the gearcase and/or driveshaft housing described herein above, thus reducing the operative lifespan of these components.”

Beginning in column 8 line 11:

“In certain examples, the controller 36 can be further configured to control an operator indicator device 52 to thereby indicate to the operator that the impact has occurred. The type of operator indicator device 52 can vary and in certain examples can include a video screen or any other visual aide for visually indicating the impact occurrence to the operator and/or a speaker or other audio aide for audibly indicating the impact occurrence to the operator.”

Beginning in column 8 line 39:

” Such high speed impact occurrences that cause the propeller 20 to leave the body of water 14 could pose a serious risk to the safety to passengers on the marine vessel 12.”

Brunswick says to reduce false positives (saying there was an impact when there was no impact) the system could sense one or more additional variables such as making sure the rate of trim exceeds that of normal trimming, the boat is trimmed beyond the normal trim range (up in the tilt range), and the engine is over revving from the propeller breaking the surface of the water (less resistance).

Beginning in column 8 line 59:

“In other examples, the present inventors have also determined that impact occurrences at high speed can also cause the marine propulsion device 10 to trim upwardly beyond a normal trim position range for that particular arrangement. The present inventors have determined that the position to which the marine propulsion device 10 is trimmed can provide an additional indication of whether an impact to the marine propulsion device 10 has occurred. Thus the controller 36 can be configured to determine that a high speed impact has occurred when both (1) the rate of trim of the marine propulsion device 10 is higher than the noted threshold value and (2) the trim position of the marine propulsion device 10 is outside of a stored “normal range” of trim positions for that particular arrangement. This combination can prevent or limit “false positive” readings, i.e., where a rapid change in rate of trim is in fact not caused by an impact occurrence.”

Beginning on column 9 line 15:

“As discussed herein above, the present inventors have also determined that it is desirable to provide improved systems and methods for determining and/or predicting future maintenance and/or repair requirements for a marine propulsion device based on current and historical impact occurrences to the device. In certain examples, the controller 36 can also or alternately be configured to calculate an impact force on the marine propulsion device 10 based upon the rate at which the marine propulsion device 10 is trimmed relative to the trim axis 30. For example, the memory of the controller 36 can be programmed with a look-up table that correlates rate of trim of the marine propulsion device 10 to impact force on the marine propulsion device 10. The correlation between rate of trim and force can be determined by historical data and experimentation (trial and error). For example, the present inventors have determined that the faster the marine propulsion device 10 is trimmed about the trim axis 30, the greater the impact on the marine propulsion device 10, and vice versa.”

Beginning in column 9 line 48:

“In some examples, the manufacturer of the marine propulsion device 10 can estimate a total cumulative force limit that the marine propulsion device 10 could withstand before maintenance or repair likely will be needed. Based upon a comparison of the resultant value calculated by the controller 36 to the total cumulative force limit, the controller 36 can be configured to control the operator indicator device 52 to indicate a remaining useful life of the marine propulsion device 10. If the resultant value calculated by the controller 36 is greater than the stored value, the controller 36 can be further be configured to control the operator indicator device 52 to provide a recommendation for necessary service and/or replacement.”

The Patent Claims

Interestingly the patent only contains 13 claims, 3 of which are independent claims (claims 1,7,9).

The leading claim, Claim #1, describes a system for detecting underwater impacts to a marine propulsion device that is trimmable. The claim goes on to include three elements (1) using a controller to determine rate of trim, (2) comparing rate of trim as determined by the controller with a stored threshold value to determine whether an impact has occurred, (3) using the controller to calculate impact force based upon rate of trim.

Only having 13 claims AND including the calculation element in Claim #1 leads us to believe they had some problems getting the patent issued. Those feelings were reinforced by the patent being filed 27 September 2016 (it took approaching 2.5 years to be issued).

A look at Public PAIR provides a view behind the scenes of prosecution of the patent. Brunswick started out with 20 claims, but in August 2017 USPO said about half the claims referred to a marine propulsion device and the other half to an impact detection system. USPTO said Brunswick had to pick one path or the other. Brunswick picked impact detection, and so doing lost the 11 propulsion device claims.

In USPTO’s non-final rejection letter dated 18 September 2017, USPTO rejected the remaining 9 claims as being indefinite for failing to particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter which the inventors regard as the invention. USPTO and Brunswick jousted over the remaining claims plus a few new claims till mid November 2018, then the patent began to move on through the system.

It looks like USPTO and Brunswick particularly fought over the US 4,734,065 Nakahama patent we included the full cover page of in our 13 December 2018 paper, Approaches to Prevent Outboard Motors From Flipping Into Boats After Striking Floating or Submerged Objects. Back then, in 1986 Nakahama tought sensing the rate of change of trim to detect impacts AND detecting when the drive was trimmed beyond its normal range. Nakahama is why Brunswick had to add the calculation element into their Claim #1.

Warranty Impact?

Brunswick’s patent makes no mention of this data being used as a variable during the consideration of warranty issues. However, it seems obvious that if you have a habit of striking stuff pretty frequently, or striking things very severely, the warranty office will look down upon you condescendingly, even for issues unrelated to parts involved during impacts.

Suzuki’s Prior Art

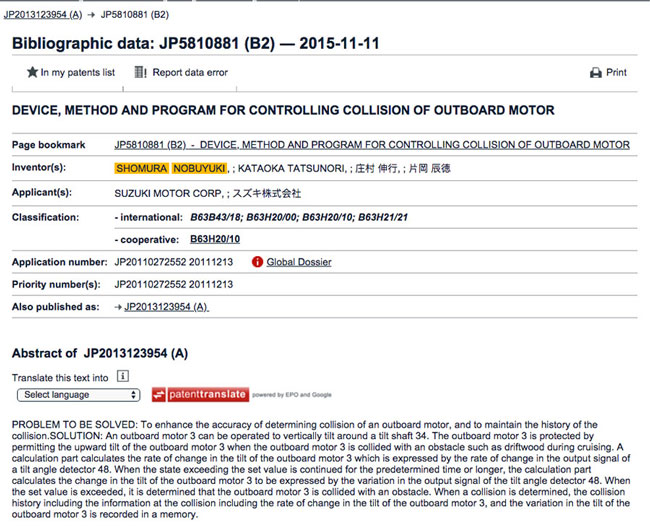

We were a bit stunned that no one cited Suzuki’s Japanese patent, JP2013123954 – 2015-11-11 titled, “Device, Method, and Program for Controlling Collision of Outboard Motor.”

Suzuki goes on to teach about the propeller revving up when it breaks the surface of the water, monitoring rate of change of trim, recording impacts, and alerting the operator during impacts.

We suspect Brunswick’s patent could have issues with prior art in the Suzuki patent if the Brunswick patent were to be re-examined.

If anybody is interested in learning more about these technologies, we do have Japanese and English versions of the full Suzuki patent.

Other Prior Art

We and others have identified many ways to detect outboards may have broken free during and impact such as rate of trim, over revving engine when propeller clears the water, and the engine being trimmed above the normal trim range. We also taught use of two or more variables to reduce false signals (false positives). We noted specifically how Mercury’s CAN-BUS control system could integrate these inputs, detect a strike, throttle back the engine and kill the engine in instances in which the outboard was detected to have broken free. A few of Brunswick’s claims (claims 7 to 13) MAY have some challenges with this prior art. Brunswick’s claims 1 though 6 require the calculation of an impact force. Only the Suzuki patent described earlier includes that element.

Alerting the Boat Operator

Brunswick’s patent teaches their system can alert the operator an impact has occurred such as by using a video screen or any other visual aide and/or a speaker or other audio aide.

Note this patent is for detecting impacts above a certain level, it is not designed to alert those on board the outboard motor has or is about to break free from the boat and may enter the boat. That is why they suggest use of a video screen, visual aid, or speaker.

Thoughts About Recording Impact Data

Recording data of this nature over thousands of outboard motors provides an opportunity to study impacts and impact severity by outboard model, horsepower, boat type, boat length, etc. This data could provide insights into how to prevent outboard motors from breaking off and flipping into boats, and insights into how to prevent people from being ejected during these events.

Thanks to Mercury Marine and Brunswick

We appreciate Mercury Marine and Brunswick working on projects related to log strikes and wish them well in this endeavor.

Update

- U.S. Patent 10,214,271 Systems for Methods for Monitoring Underwater Impacts to Marine Propulsion Devices. Issued to Brunswick Corporation. 3 March 2020.

The 10,214,271 patent was filed 6 December 2018 as a followup patent to the patent this article covered.

We noticed the patent file wrapper for this second patent included a 5 March 2019 filing in which Brunswick alerted the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to the Suzuki patent we mentioned above as potential prior art. The examiner (Mr. Venne, the same examiner for both Brunswick patents), filed a report saying he examined this second patent relative to the Suzuki patent. But we saw no notes in the various claim objection to it. That could be due to them not having the full English translation vs some pages off of Google Patents.